Anne Brice, UC Berkeley

If you’ve ever seen letters from the 1800s, it’s striking how differently Americans communicated with each other compared to today. Aside from their often-pristine penmanship, the effusive language friends used to express their fondness for each other is remarkable.

In 1851, at age 20, poet Emily Dickinson begins a letter to her close friend Susan Gilbert, who’d recently moved to Baltimore for a teaching job and to whom Dickinson would write frequently:

Emily Dickinson in 1847, at age 17. Around this time, Dickinson met Susan Gilbert, to whom she wrote deeply affectionate letters throughout her life.

Will you let me come, dear Susie — looking just as I do, my dress soiled and worn, my grand old apron, and my hair — Oh Susie, time would fair to enumerate my appearance, yet I love you just as dearly as if I was e’er so fine, so you wont care, will you? I am so glad dear Susie — that our hearts are always clean, and always neat and lovely, so not to be ashamed. I have been hard at work this morning, and I ought to be working now — but I cannot deny myself the luxury of a minute or two with you.

“Letters sent between friends are often full of the kinds of loving and affectionate language that today we would only associate with romantic or sexual relationships,” says Sarah Gold McBride, a UC Berkeley historian and lecturer in American studies who specializes in the social and cultural history of the 19th-century United States.

She says that because the leisure worlds of men and women were mostly separate, especially in the late 19th century, norms of homosocial friendship — friendship between people of the same gender — were different, too.

“On one hand, it is fully possible that people who are writing to each other in these ways expressed physical intimacy with each other in ways that we would now recognize as a sexual relationship,” says Gold McBride. For example, scholars have long surmised that the connection between Dickinson and Susan eclipsed what we today would consider a platonic relationship.

But, Gold McBride adds, “it is also the case that norms of homosocial-emotional communication were different in the past than they are in the present.”

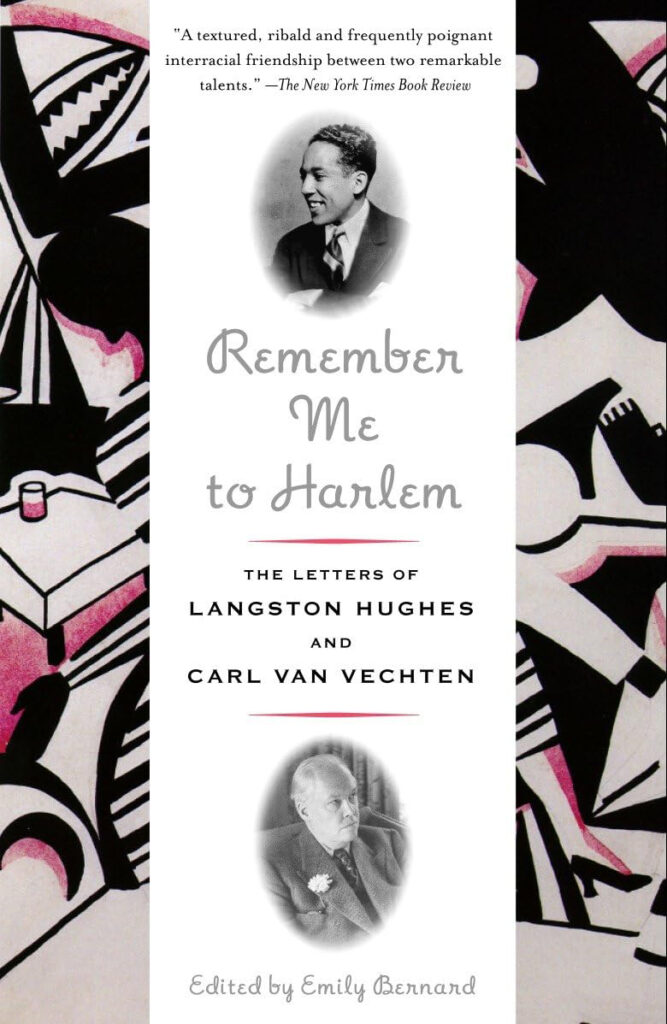

To do this, Gold McBride and Palmer have their students look at all sorts of media, from letters between the writers Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten in the 1920s to the 1991 movie Thelma & Louise to the 2021 book Big Friendship: How We Keep Each Other Close.

Students also explore the ways we do (or don’t) communicate affection for our friends today. It’s something Gold McBride says especially resonates with men in the class, who talk about how norms of contemporary American masculinity stigmatize emotional closeness in their friendships with other men.

It’s not just shifts in norms and attitudes that influence how we make friends and maintain friendships, says Palmer, who specializes in 20th-century popular and mass culture. The modes of communication that we use to stay in touch with each other also have a big impact on what our friendships look like.

In one lecture, Palmer introduces their students to the Princess telephone, which came out in 1959 and was designed to fit into the frilly aesthetics associated with a teenage girl’s room at the time.

“It came in pastel colors — pink, canary yellow, robin’s egg blue,” says Palmer. “Ads are very pointed in placing the telephone as a marker of friendship, as a tool of making and maintaining friendship.”

In a TV ad for the phone, a fairy godmother-sounding narrator talks in a gentle, aspirational tone:

This is the room of a princess — a teenage princess — because she has a personal extension phone for the privacy and personal freedom teenagers want and need.

If handwritten letters are a souvenir of friendship in the 19th century, and the Princess telephone is an artifact of what friendship looked like in the 20th century, then what represents what modern friendship looks like? What items might go into a friendship museum?

“I’d want to include the Beyoncé and Miley Cyrus duet from Cowboy Carter, ‘II Most Wanted,’ in part because it is absolutely a friend anthem, but it also has a dynamic that’s similar to Thelma & Louise,” says Palmer. “It is about a kind of love, a complicated love: ‘I love you, I’m sick of you, get your hand off of me, touch me.’ You know, this sort of thing.”

“A display case full of friendship bracelets exchanged at the Eras Tour,” says Gold McBride. “That captures two elements of contemporary friendship: parasocial relationships and the way that Taylor Swift, in particular, has really made herself a friend to all of her fans in such a way.

“It’s such a beautiful act of an object as a carrier of friendship. It straddles this really interesting middle ground between parasocial friendships and in real life, IRL, friendships.”

Taylor Swift fans — known as Swifties — make and exchange friendship bracelets as a way to connect and build community at Swift’s concerts. The bracelets became a defining tradition among Swifties during the recent Eras Tour.

With the rise of social media, parasocial relationships — one-way connections where people feel like they know someone they’ve never met in person, like a celebrity or a public figure online — have become increasingly common and complex. Research has found that more than half of Americans have likely been in parasocial relationships.

While social media can make it easier to connect with people who have similar identities or interests, like it does for Taylor Swift fans, it can also make it easier to forget what it takes to build and keep meaningful relationships. Palmer explains that dynamics on social media platforms, where an additional emphasis is placed on the number of friends or followers one has, have changed the way young people approach friendship today — and not always for the better.

“I hear quite often a lot of anxiety from our students about, ‘How do I make friends? How do I keep friends? How do I even know who could possibly be a friend?’” says Palmer.

But Gold McBride says that by interrogating friendship throughout history, students can reflect on how their modern friendships feel and possibly think about them in a deeper way than they had before.

After meeting in 1924, writers Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten maintained a lifelong friendship and correspondence until Van Vechten’s death four decades later. In their letters, which Gold McBride and Palmer look at in their class, the writers frequently expressed mutual admiration and appreciation for each other’s work and friendship.

“There’s something to seeing how much care and labor it takes to maintain a friendship when your mode of connection is writing a letter back and forth,” says Gold McBride. “Perhaps these examples of how people have gone to great lengths to do so in the past will inspire students to tend to their own friendships with similar intentionality.”

“I’m smiling now because I’m remembering one student who did tell me that they had started working on improving their penmanship so that they could actually start writing letters to their friends,” says Palmer, “which I thought was so sweet, so touching.”

Gold McBride and Palmer say that even though friendship in America has transformed significantly throughout history, you can still see many of the same characteristics today.

“I remember, once I had a student who said, ‘Gosh, I always assumed people who lived 150 years ago were all very prim and proper’ — the sort of greatest hits you see in a textbook — ‘but they’re just as messy and petty and silly as we are today.’ I love that comment,” Gold McBride laughs.

Although our technologies and the way we interact with media has changed, she says, friendship in its many forms throughout the decades shows us we’re a lot more similar than we are different.