Jim Logan, UC Santa Barbara

By any measure, John Wesley Gilbert led an extraordinary life. Born into slavery, he became one of America’s great scholars — a classicist, a linguist, an archaeologist and an educator. His drive, faith and commitment to education took him from the poverty of his native Georgia to Brown University, Greece, Africa and beyond.

And yet Gilbert, who was also a fierce advocate for interracial cooperation, is little known to the general public. Now, a new biography aims to correct that oversight.

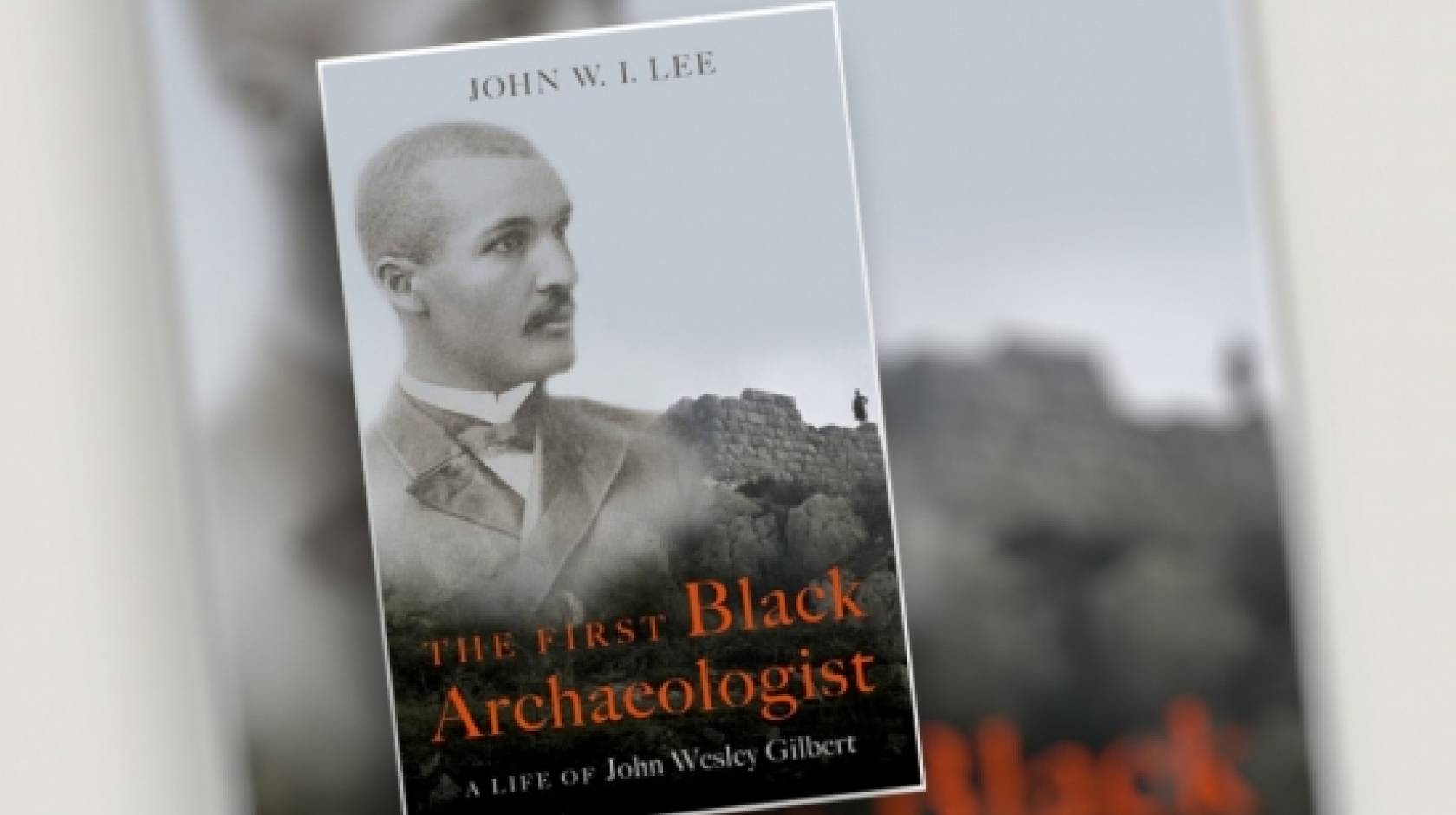

“The First Black Archaeologist: A Life of John Wesley Gilbert” (Oxford University Press, 2022) by John W.I. Lee, an associate professor of history at UC Santa Barbara, meticulously traces the pioneering scholar’s rise to national prominence in an era when African Americans often faced obstacles in obtaining even an elementary education.

Lee, whose research usually focuses on ancient Greece and Persia, found kinship with the man who was the first African American to attend the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the American School) in 1890 and 1891. Lee was a student there in 1996 and 1997.

“I literally walked in his footsteps,” Lee said, “when I visited the Acropolis, the battlefield of Marathon, and other ancient sites he had seen during his time in Greece. And in the American School library I wrote my first scholarly article in the same room where he had written his master’s thesis a century before. It was this connection of place that drew me on to explore John Wesley Gilbert’s work in Greece, and then to tell the story of his extraordinary life in its entirety.”

Gilbert — who mastered French, German, classical and modern Greek, Latin and the African languages Otetela and Tshiluba — was among the first Americans of any ethnicity to do professional archaeological work in Greece, the Mediterranean or Near East. In addition to excavating at the ancient city of Eretria, Gilbert wrote a thesis about ancient Athens that helped earn him a master’s degree from Brown — the first it awarded to an African American.

Indeed, Gilbert’s life was a study in breaking barriers. He was among the first students at the Methodist-sponsored Paine Institute (now Paine College), an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in Augusta, Georgia. He later became Paine’s first black instructor and taught there for more than 30 years. In that time he worked closely with the school’s white president, the Rev. George Williams Walker, who became a lifelong mentor and friend.

“Gilbert provides an inspiring example of an African American pioneer who rose from slavery to reach the heights of U.S. education, and who devoted his life to service as an educator, community leader and missionary,” Lee said. “His life also opens a window to appreciating the enormous flowering of African American education during and after the U.S. Civil War — those students and teachers deserve recognition as one of our nation’s greatest generations.”

Since his death in 1923, Gilbert has been known best for his missionary work in the Belgian Congo in 1911 and 1912. He went as a representative of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (now the Christian Episcopal Church) or CME. His partner in the mission was Walter Russell Lambuth, a white bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, or MECS.

The pair helped establish a mission at Wembo Nyama in central Congo that still exists today. Both the CME and the MECS (and now the United Methodist Church) traditions have long revered Gilbert and Lambuth’s Congo mission as part of their denominations’ shared history.

Their partnership highlights Gilbert’s lifelong commitment to interracial cooperation, which was part of an important but sometimes overlooked thread of 19th century U.S. history, Lee said.

“Gilbert’s beliefs,” Lee said, “were shaped by his own youthful experiences at Atlanta Baptist Seminary (the forerunner of Morehouse College), where he saw Black and white teachers working in the common cause of Black education, and by his career at Paine College, which opened its doors in 1884 to educate Black students as a cooperative venture of Black and white Southern Methodists.”

For Lee, the years researching and writing about Gilbert have been as much a labor of love as a work of scholarship. Given that, it’s not entirely surprising to learn that he will donate any royalties from the sale of the book to Paine College and the William Sanders Scarborough Fellowship of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

“It’s just the right thing to do,” he said. “Professor Gilbert’s story belongs to Paine College, where he was the school’s first student, first graduate and first Black professor; I’m only the messenger. Academic books don’t tend to sell in huge numbers, but perhaps more people will buy a copy knowing that they are helping support Paine and also the Scarborough Fellowship, which the American School established to honor Gilbert’s fellow African American scholar, who wanted to go to Greece during the 1880s but could not find funding.”