As an army infantryman in Iraq, Nathan Goncalves saw his share of grueling battles. But none quite prepared him for the transition from military to civilian life.

“You come back from combat and you’ve seen and faced atrocious things, but everyone else’s life has gone along as it always has,” said the UCLA alum. “Nothing around you makes sense anymore. Everything just seems so trivial.”

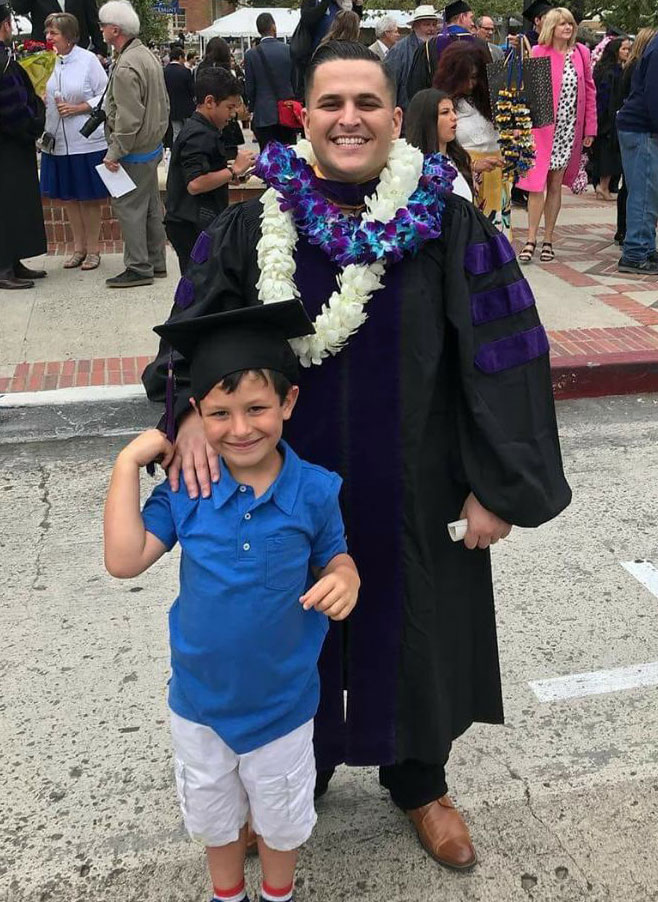

Goncalves overcame post-traumatic stress disorder and an addiction to painkillers to graduate from UCLA and earn a law degree from the school last year. He now provides free legal assistance to veterans as they reintegrate into civilian life.

For him, it is part of the military credo to never leave a fellow soldier behind. It’s a bedrock principle held close to the heart by many UC student veterans, who are turning their skills and education toward helping other service members build productive lives back home.

Offering legal advice, and a lifeline

In spring of 2009, Goncalves was on a transport mission in Iraq, when a 500-pound roadside bomb exploded, killing a fellow platoon member and leaving another as a quadruple amputee. Goncalves suffered spine fractures and a torn rotator cuff, and ended up with long-term emotional and physical impacts. His struggles were magnified when he returned stateside and faced the pressures of adapting to life outside the military.

Iraq war veteran Nathan Goncalves with his son Noah at his graduation from UCLA.

Goncalves considers himself lucky: Veterans benefits helped pay for counseling, physical rehabilitation and college. With his health problems under control, he was able to enroll at his dream school — UCLA — and then went on to complete his law degree there in 2017.

“I am sort of seen as the poster child for what happens when veterans benefits work as they’re supposed to,” he said.

He’s acutely aware that others haven’t had it so easy. Many face bureaucratic and legal obstacles to claiming their benefits. Others face homelessness and run-ins with the law as a result of addiction and mental health struggles.

Wanting to help, he volunteered with UCLA's Veterans Legal Clinic, which opened in 2017 to provide free legal services to homeless and at-risk vets.

Now, with his newly-minted law degree in hand, Goncalves provides free attorney services for those who have successfully gone through counseling for addiction and mental health issues to reconnect with children and family members.

“There is a huge influx of troops coming back from Afghanistan and Iraq, and we have to broaden our scope of what we’re doing to get people back on their feet,” said Goncalves.

Unlocking opportunity and a sense of purpose

Derek Herrera received his Purple Heart at the Bethesda Naval Hospital after being shot by a sniper. He has started a medical device company to help people who are paralyzed.

Legal difficulties are just one kind of obstacle returning military personnel encounter. Across UC campuses, veterans are finding ways to give their fellow soldiers a leg-up, whether its providing moral support to incoming students or looking for other ways to help.

Entrepreneur Derek Herrera, for example, has made it his mission to help other disabled vets start their own businesses.

A Marine special operations officer, Herrera was struck by a sniper’s bullet in 2012 while conducting combat operations in Afghanistan’s Helmand province. The injury left him paralyzed from the waist down.

Upon receiving a Purple Heart and being medically discharged, he enrolled in UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, where he launched Spinal Singularity, a company that aims to improve the quality of life for catheter users by improving how they manage bladder function.

His product — now in clinical trials — could provide an alternative to the external catheters that people use to drain their bladders. Hererra has developed an extended use, internal catheter that operates with the touch of a button.

“This could help millions of people worldwide who are paralyzed confront one of the challenges they face on a daily basis,” Herrera said.

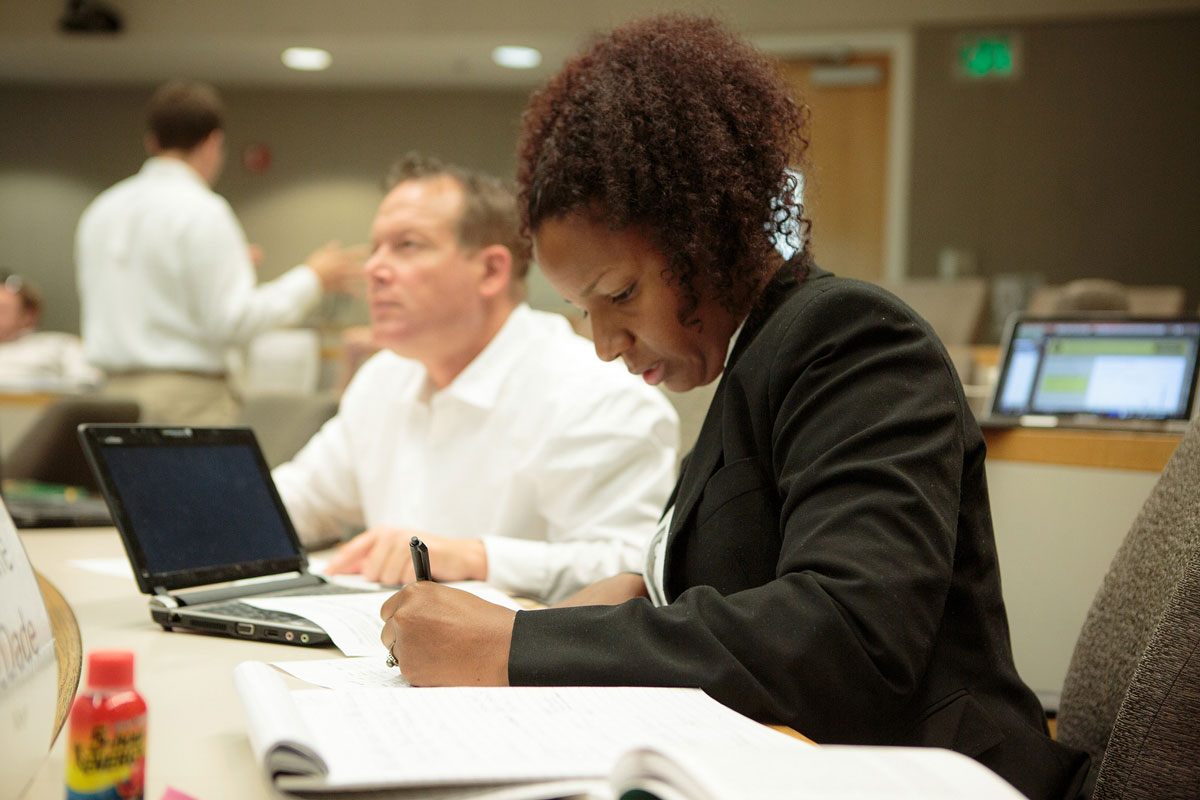

Students at UCLA’s Entrepreneur Bootcamp for Veterans, which helps those disabled in the line of duty launch their own businesses.

With Spinal Singularity now getting off the ground, he mentors other disabled vets through UCLA’s Entrepreneurship Bootcamp for Veterans, aimed at helping disabled veterans find a career path and meaning through starting their own businesses.

“The key thing I benefitted from in starting a business is being able to pursue something with the same level of impact and purpose that one has in the military. That has provided a lot of motivation,” Herrera said.

Turning platoon mates into business partners

With their determination, work ethic and singular focus, veterans have the skill set to succeed as entrepreneurs. But they need connections and a strong network.

Marine Corps veteran Michael Hayden hopes to provide that through Veteran Ventures, a 10-week accelerator program at UC San Diego that has just finished its first year. The program draws on participants’ camaraderie and sense of duty to help them form fruitful business relationships.

Participants learn how to deliver an elevator pitch, write a business plan and find capital. But they also work together to assess each other’s ideas.

Michael Hayden, left, served in the Marine Corps for 21 years and now helps veteran entrepreneurs launch startups out of UC San Diego's Basement. Here he is networking with former QUALCOMM CFO David Hind.

“We look at: What works? What’s problematic? What would make this even better? Our motto is, ‘No one of us is smarter than all of us,’” Hayden said.

The approach has yielded some ingenious and even improbable ventures, from an immersive virtual sleep therapy to treat PTSD-related insomnia to a mail-order business that creates and delivers beef jerky bouquets.

“There’s real honest feedback from people you can trust,” Hayden said. “It’s a band of brothers with no ulterior motives but to help each other get their ideas off the ground.”

A powerful reminder of all there is to live for

Brian Vargas, center, shares a laugh with another student veteran. The Cal Veterans Services Center is a place for Vargas and others to unwind and regroup.

For UC Berkeley student Brian Vargas, completing a master’s degree in social welfare, his number one mission since returning from service is preventing veteran suicides.

Vargas was wounded while on deployment with the Marine Corps in Iraq when an ammunition drum exploded in his face. He spent months in the hospital recovering and undergoing multiple surgeries and, during that time, lost a number of fellow soldiers to suicide.

He vowed to go back to school and get a degree in social welfare to help returning combat veterans — a pledge that is now reality.

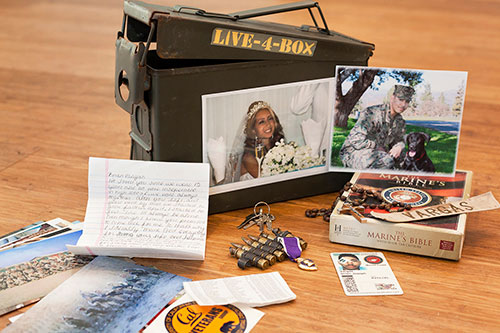

As a prototype, Vargas put together his own Warrior Box.

After transferring to UC Berkeley in 2013, Vargas co-founded the Warrior Code, a project to prevent combat veteran suicides. He also created the Warrior Box, an ammo box that veterans create, filled with tangible reminders of all the things they have to live for: pictures of loved ones, letters, medals — and most importantly — a signed contract in which they promise to do themselves no harm.

In his own box are his wedding vows and pictures of his wife, Monica — a childhood sweetheart — the shrapnel that was removed from his body, his Purple Heart, pictures of his Marine Corps unit and a sticker from the Cal Veterans Club as a reminder of his school comrades.

He wears another recovered piece of shrapnel around his neck. “Sometimes, as I’m going about my day, it’ll poke me. It’ll be a reminder that, no matter how difficult things get, I’ve been through worse — and I can get through this.”

Easing the transition from combat to college

Military training can make it difficult for veterans to feel comfortable asking for help, said Navy veteran Emerald Liu, a biology graduate student at UC San Diego. That’s what makes her work as a peer mentor so important.

Veteran peer counselor and graduate student Emerald Liu at a celebration for UC San Diego student veterans.

Returning from service as an aviation technician, Liu had her own difficulties with the adjustment from military to campus life. For her, the hardest part was staying motivated in an unstructured academic environment.

“In the military, if you do well, you would get a promotion or a commendation. In the academic setting, it’s a bit different. Especially in research, you can feel like you’re doing a great thing and not get anywhere,” she said.

“I navigated the system with a lot of help from a lot of people,” Liu said. She wanted to do the same for others who might be less inclined to seek those services.

She can be found most days at the Veterans Center on campus where she works as a trusted confidante, offering everything from a sympathetic ear to advice on finding tutoring to deciphering financial aid documents.

She also sees it as part of her job to be a pair of eyes and ears on campus, on the lookout for student veterans who might need someone to reach out to them.

“Veterans can be reluctant to seek out support,” Liu said. “It’s crucially important to be able to get help from someone who has shared their experiences.”

Visit http://veterans.universityofcalifornia.edu/ to learn more about the resources available for UC's military-affiliated students across our campuses.

Top photo: iStock/MivPiv