Dan White, UC Santa Cruz

This spring quarter, UC Santa Cruz Humanities students immersed themselves in the story of three Hawaiian princes who introduced surfing to the United States in the late 19th century, using Santa Cruz to launch a sport that became a cultural phenomenon.

The ten-week public history course, taught by UC Santa Cruz Humanities Dean and History Professor Jasmine Alinder, brought students face-to-face with the complexities of community storytelling, colonial legacies, and cultural continuity.

Designed as a project-based learning class, the course partnered with the Museum of Art and History in downtown Santa Cruz to create interactive learning tools—known as “history trunks”—for K–12 teachers to use with their students, based on the MAH exhibition, Princes of Surf 2025: He’e nalu Santa Cruz, which opened on July 18 and runs through January 4, 2026.

The exhibition commemorates the 140th anniversary of surfing’s documented arrival on the mainland.

“I didn’t know anything about the history of surfing before this class,” Alinder admits. “But what we learned was both fascinating and necessary.”

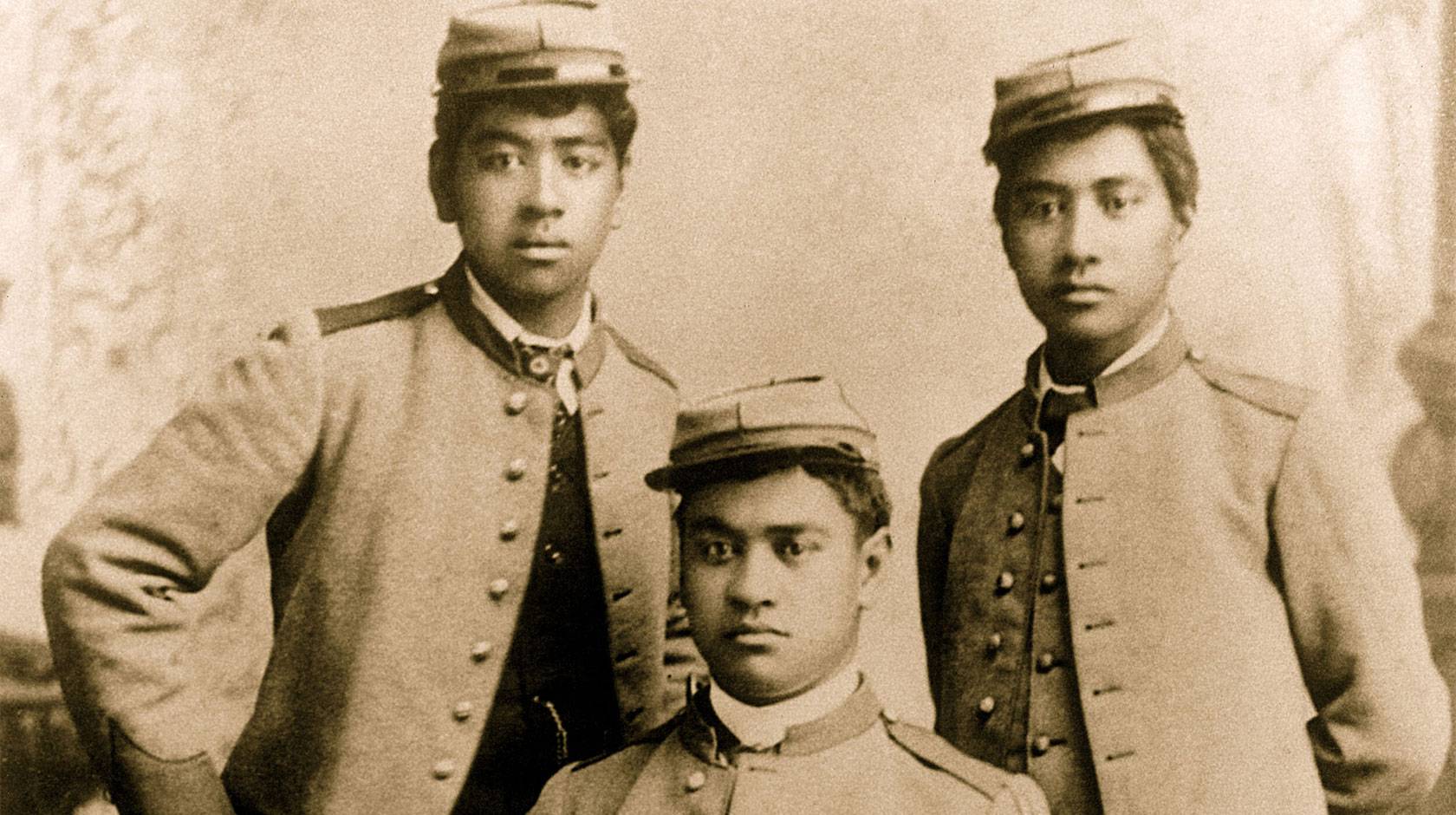

In the MAH exhibition, visitors are discovering how the Hawaiian princes David Kawānanakoa, Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, and Edward Abnel Keliʻiahonui introduced surfing to the U.S. mainland in Santa Cruz in 1885, forever altering the region’s connection to the ocean.

Reclaiming a global origin history

While studying at a military school in San Mateo, Kawānanakoa, Kalanianaʻole, and Keliʻiahonui spent the summer of 1885 in Santa Cruz with Antoinette Swan, a Hawaiian-born woman of royal descent who had settled in the area.

The princes crafted large, redwood o’lo boards weighing up to 175 pounds.. Swan lived near the San Lorenzo River, so the princes floated them from the mouth of the river, where there is a now-popular surf break.

“The princes did a surfing demo that drew a lot of attention,” Alinder said. “When we think of the history of surfing in California, of course, there is also an earlier Indigenous history of interaction with the ocean’s surf and tidal zones.”

Local newspapers recorded the princes’ ride, but stereotypes of surfing as a white, male-dominated sport have long overshadowed the cultural significance of the moment. The MAH’s exhibition and Alinder’s class aim to correct this misconception.

The students’ work complements an exhibition that features historically accurate replicas of the princes’ boards, loaned artifacts from Hawaiʻi, and a renewed look at Swan’s overlooked story as a woman surfer and cultural bridge between Hawaiʻi and California.

Surf, students, and storytelling

Alinder’s class met weekly at the MAH, splitting time between academic study and hands-on collaboration with museum staff and community experts.

Students designed educational trunks for elementary, middle, and high school levels—following a successful model previously used for the museum’s “Queerstory” exhibit on local LGBTQ+ history.

“We wanted to create something that lived beyond the exhibit,” said Alinder. “These trunks are filled with hands-on activities and discussion prompts to help young people challenge assumptions about who surfs, who’s represented in history, and who’s been excluded.”

“Queerstory” has three trunks—one for elementary, one for middle, and one for high school students.

“We used that model to design learning activities to make history trunks for the history of surfing exhibition,” Alinder said. “This is a deeper way for K–12 students to engage, and ideally, it lasts beyond the exhibition.”

The surfing history trunks are still in development. Students designed six prototypes—two each for elementary, middle, and high school levels—which are being refined over the summer in collaboration with Leo Coletta, a UC Santa Cruz undergraduate who double majors in History and Politics.

Coletta is now a Museum Education Fellow with the Humanities EXCEL internship program at the MAH. Final versions of the trunks will be finished by the end of summer and used in local classrooms to spark deeper discussions about surfing, colonization, and cultural identity.

A revelatory experience

Alinder’s students found the class revelatory, regardless of their previous exposure to local surfing lore.

Benyamin Alfaro (Merrill, ‘25, History and Education) was enthusiastic about the surfing history trunks that he helped prepare. “It is not enough for information to stay at a museum or a university,” Alfaro said. “This information needs to be spread to our K-12 educational areas. Public history is incredibly active and very real; it is important to show K-12 students how the world around them is moving and breathing, not stagnant.”

“When I first saw the listing, I had to re-read the description because I thought it was too good to be true!” said Wyatt Dana (Stevenson, ‘25, History.) “Surfing has been a passion of mine since I was in childhood, and History, although a much newer interest, has become a significant part of my college experience. I also liked the education component, and was excited to dip my toe into the idea of developing curriculum, as teaching is a career path I am considering.”

The class’s featured guest speakers included UC Santa Cruz faculty, museum professionals, and surfing diversity advocates like Esabella “Bella” Bonner, founder and executive director of Black Surf Santa Cruz, which promotes mental, physical, spiritual, and communal healing through surfing, recreation, education, and wellness, with a strong focus on inclusivity, justice, and equality.

Bonner shared insights about access, representation, and the intersections of race, gender, and geography in surfing culture today.

The class also connected with scholars such as Isaiah Helekunihi Walker, author of Waves of Resistance: Surfing and History in 20th Century Hawaii, a study of surfing as an act of Indigenous resilience against colonial and military pressures in Hawaiʻi.

Despite being a history class, the course wasn’t confined to the archives. Alinder and 16 of her 25 students (only one of whom identified as an avid surfer) took a group surf lesson through Surf School Santa Cruz, led by a local surfer who had braved the gigantic waves at Mavericks.

For Alinder, whose public history work usually focuses on civil rights and Japanese American incarceration, this dive into surfing history was both experimental and deeply rewarding. “I’ve taught many public history and museum studies courses, and this topic wasn’t part of my normal teaching repertoire,” she says. “But it was fun. It reminded me that local history isn’t just something we read—it’s something we build, share, and question together.”

The course and the Heʻe Nalu exhibit both arrive at a moment when Santa Cruz—and the broader surfing world—is reckoning with its layered past.

“In organizing this exhibition, we want to share a few links to a broader conversation, to honor our relationship with the water that began before the princes came to Santa Cruz,” said Marla Novo, deputy director of MAH. This isn’t the beginning or the end of the narrative. It continues in the ways we connect with each other, share and listen, one wave at a time.”

The exhibition commemorates the 140th anniversary of surfing’s documented arrival on the mainland. It is co-sponsored by The Humanities Institute at UC Santa Cruz