Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

America is the global leader in developing new treatments for deadly diseases. But funding for biomedical research is under threat. Join UC as we speak up for science.

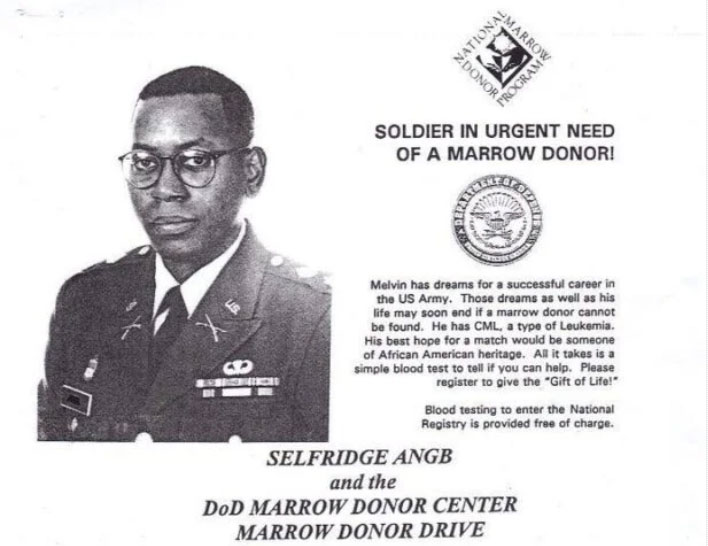

Federally funded science is critical to discovering new treatments for disease. Just ask Melvin Mann, who was a 37-year-old Army major when doctors diagnosed him with an aggressive and deadly blood cancer called chronic myelogenous leukemia, or CML.

“They said the only cure was a bone marrow transplant, but in 1995, the year of my diagnosis, it was very hard to find a match,” Mann said. Absent a transplant, his doctors gave him three years to live. “So I needed something new to come along,” he said.

The search for a life-saving treatment

In the following years, Mann enrolled in clinical trials, but none of the drugs he was testing worked. “By the time that three-year mark came around, I’d wake up, drink two cups of coffee, and go right back to sleep for the next eight hours,” he says. He lost 30 pounds, and his white blood cell count, a measure of the progression of his disease, ticked upwards. He started to “make peace with what was going on,” he says — that he likely wouldn’t live to see his 8-year-old daughter start high school or get her driver’s license. His doctors told him he’d nearly run out of options for experimental treatment.

Nearly, but not entirely. “I asked my doctor, ‘Are you sure there aren’t any more drugs?’ and he said, ‘Well, we’ve got one in the lab that’s close,’” Mann says. This formula represented a new approach to treating his condition: It was designed to inhibit the cancer-causing effects of a chemical called tyrosine kinase, a protein our bodies produce to drive cell division. People with CML produce too much tyrosine kinase, which in turn causes overproduction of white blood cells, causing illness.

Mann was among the first people to be treated with this new tyrosine kinase-inhibiting drug in a clinical trial. “And that was the drug that saved my life,” he says. As soon as he started taking the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, blood tests showed his body producing fewer white blood cells. Soon, his energy came back, and he put on weight. Ten months after starting treatment, he ran a marathon.

Mann running his first marathon after his health was restored by a new drug called Gleevec.

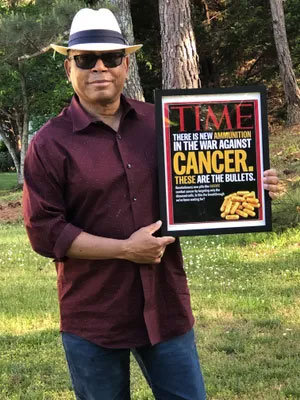

Mann commemorated more than two decades of treatment by revisiting a 2001 TIME magazine cover story calling Gleevec "new ammunition in the war against cancer."

How “miracle” medicines emerge from federally funded science

The drug, marketed as Gleevec, worked so well for Mann and other trial patients that the FDA accelerated its approval for use nationwide. Before Gleevec, most people diagnosed with CML died of their disease within five years. Today, with treatment, CML patients can expect to live long, healthy lives.

"That drug was a miracle,” Mann says — but he doesn’t chalk it up to serendipity. He’s alive today, he says, because scientists in academic and government labs across the country had been working for decades to learn what caused his disease and how to stop it. Federal funding for exploratory research powered this progress every step of the way.

“The research that saved me started way before I was diagnosed, even going back to the 1950s,” Mann says. That was when federally funded scientists at the University of Pennsylvania first noticed something different in the DNA of people with CML. In the 1970s, a geneticist at the University of Chicago used funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the federal Atomic Energy Commission to identify the exact DNA mutation that’s implicated in the disease. Researchers at the federal National Cancer Institute identified the mutated gene that caused the body to produce too much tyrosine kinase in the early 1980s.

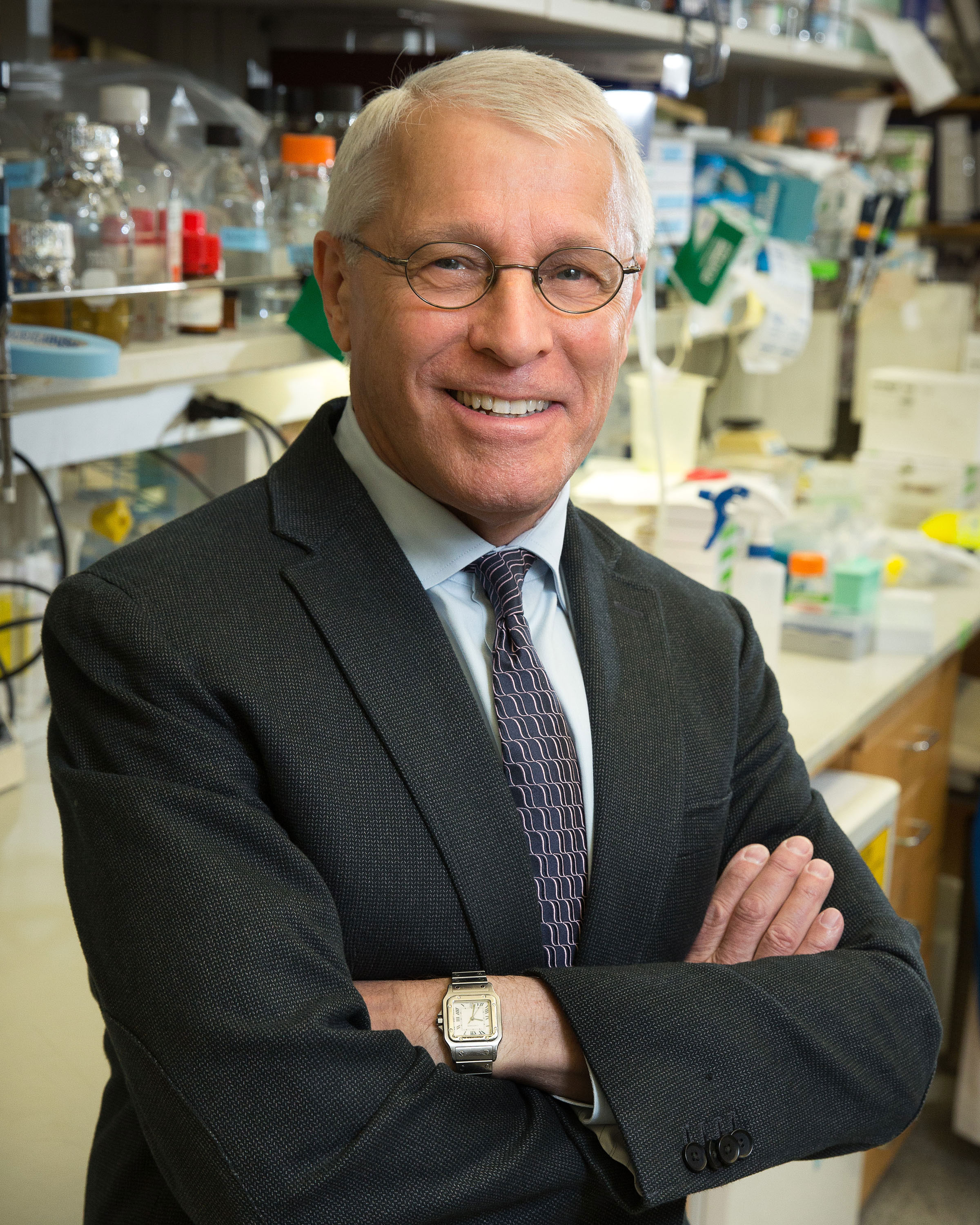

And in the mid-1980s, UCLA professor Owen Witte discovered that this abundance of tyrosine kinase caused CML symptoms. Witte’s NIH-funded work led to research into molecules that could inhibit tyrosine kinase at Oregon Health & Science University, and pharmaceutical company Novartis began work on manufacturing the drug in the 1990s.

“This is how innovation has worked in this country: The federal government spends money on basic research. Basic research produces discoveries that can be exploited by the drug industry to make drugs that change the lives of patients,” says Witte, who today is a distinguished professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics at UCLA.

The many returns of government-backed science

Today, about 9,000 Americans are diagnosed with CML each year. It’s a huge number when you think about the life that was once lost with each diagnosis — but that’s not necessarily how pharmaceutical companies think. “No drug company was going to invest in exploratory research for that small an amount of people, because there’s no way to know that they’d get a return on their investment,” Mann says. “Once you get started, a drug company can see the promise and where it's going. But without the initial federal funding, you never get to that first step.”

Gleevec became the first drug in a whole new segment of the pharmaceutical industry, which now makes tyrosine kinase inhibitors for dozens of diseases, including other forms of cancer, autoimmune conditions and metabolic disease, Witte says. He has been widely recognized for his contributions to understanding and treating blood cancers, work made possible by decades of federal research grants.

“Millions of people are taking these medicines and are walking around leading relatively normal lives, instead of getting sicker and dying. And those pharmaceutical companies are keeping a lot of people employed and generating a lot of economic activity,” Witte says. “I could not imagine a better use of federal funding than that.”

Mann and his daughter, Patrice, on the day she graduated from medical school.

Pushing for faster progress

Thanks to this virtuous cycle, Mann was there as his daughter, Patrice, got her driver’s license, graduated high school and college and eventually medical school. With his health restored, he earned a master’s degree in education and taught English literature to middle and high schoolers in Atlanta. He ran more races. And ever mindful of the people with CML who died before a treatment arrived, and grateful for the science that saved his life, he has gotten deeply involved in advocacy around issues affecting people with cancer. He and his wife, Cecelia, make regular trips to the Georgia Statehouse and to Washington, DC, meeting with elected leaders on a range of issues, including strengthening Medicaid and Medicare, so people without private insurance can still get the care that saved his life.

And lately, Mann has been speaking more about the importance of federal funding for basic research, as America's commitment to funding basic research wavers. Right now, Congress is considering spending bills for the coming year, and the administration’s proposal would cut funding for science agencies like the NIH and the National Science Foundation.

Mann says these cuts could determine the future for the CML community, for one thing. Though people diagnosed with CML today can expect to live long, healthy lives with medication, that’s not the same thing as a cure. “I have to take a pill every day, but maybe in the future people won’t have to,” he says. “Eventually, if they keep at it, they will find a cure.”

What’s more, CML is one of thousands of so-called rare diseases, many of which remain untreatable, let alone incurable. While each of these conditions may affect just a few dozen or a few thousand people, collectively their burden is massive: the NIH estimates that 30 million Americans, or roughly 1 in 10 of us, live with a rare disease. So while Mann’s family got their miracle, he knows there are millions more people still waiting for theirs.

If the government pulls back on funding basic research, progress for those families “would come to a standstill,” Mann says. “It would just be a big red light. It would just stop, and you’d have to just be satisfied with what you have now.”