This story is going to be spoiled right from the beginning, but don’t worry. According to research by UC San Diego psychology professor Nicholas Christenfeld, spoilers don’t ruin a story: They make you enjoy it even more.

One more spoiler: In the movie “The Usual Suspects,” Kevin Spacey is Keyser Söze. If you haven’t seen it yet, wow, you’re really going to love it now.

Christenfeld’s interest in storytelling was sparked by his daughter’s elementary school homework assignment.

“She wrote a story where someone wakes up in the morning and does one thing, and does another thing, and does another thing…and then goes to sleep,” said Christenfeld. “I tried to explain to her, no, no – stories need arcs. There needs to be a challenge, and the person overcomes the challenge or succumbs to it, and then has learned something at the end.”

But as he was explaining it, he paused to think. Does fiction really have to work that way? What makes people enjoy or not enjoy a story?

“Fiction is a peculiar thing when you stop and think about it,” said Christenfeld. “People spend enormous amounts of time devoting themselves to completely made-up stories. I became curious about what it is about fictional narratives that attracts people.”

Enjoying the spoils

If suspense, surprise and satisfying resolutions are the heroes that save a story, spoilers are the villains that try to, well, spoil everything. Or at least that’s how they’re portrayed.

“We asked lots of people, ‘Do spoilers ruin experiences for you?’” said Christenfeld. “The vast majority of people say ‘yes.’”

If you’ve ever gone to considerable lengths to avoid hearing who won the big game, who became the latest dragon snack on “Game of Thrones,” or who Keyser Söze really is (it’s Kevin Spacey), you’re in good company.

Intuitively, killing the surprise seems like it should make a narrative less enjoyable. Yet research has found that having extra information about artworks can make them more satisfying, as can the predictability of an experience. So Christenfeld decided to put spoilers to the test in the most straightforward way possible: by spoiling stories for people.

In the initial experiment, his team had subjects read short stories from various genres. One group simply read a story and rated how much they liked it at the end. The other group did the same, but the researchers spoiled the narrative, as if by accident, by giving them a short introduction.

“’In this, the classic story in which the woman murders her husband with a frozen leg of lamb…,’” said Christenfeld nonchalantly as an example.

“What we found, remarkably, was if you spoil stories they actually enjoy them more.”

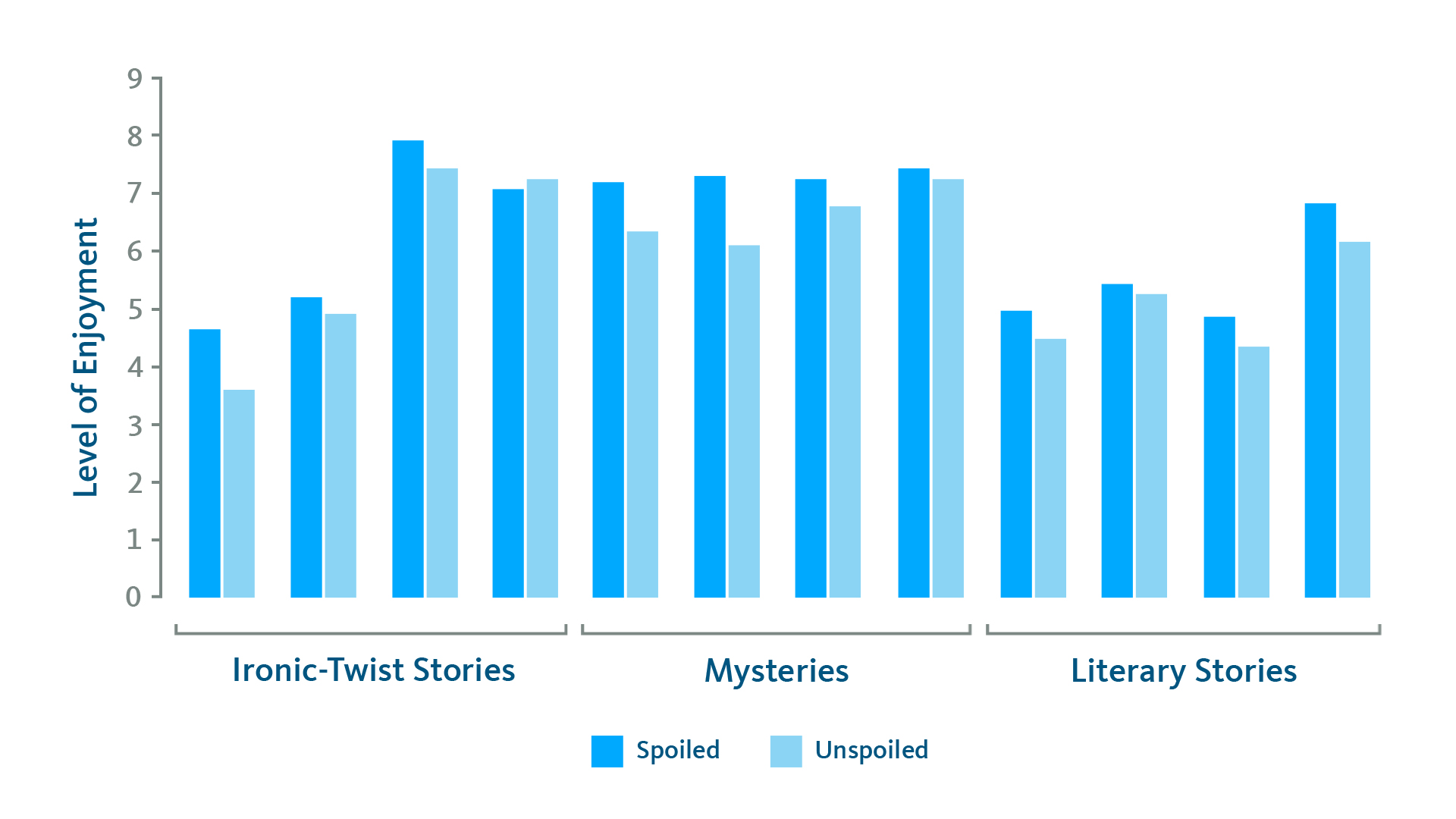

Christenfeld repeated the experiment with three different genres: mystery stories containing a “whodunit” moment; ironic twist stories, where a surprise ending crystallizes the whole story; and literary fiction with a neat resolution.

“Across all three genres spoilers actually were enhancers,” said Christenfeld. “The term is wrong.”

Source: Leavitt and Christenfeld, 2011

Ironically, a study about spoiling surprise endings had a surprise ending.

In retrospect, Christenfeld thinks he should have seen it coming all along.

“When people go to see ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ they don't think ‘Don't tell me how it ends!’” said Christenfeld. “’All's Well That Ends Well’? That one ends well. So there isn't any thought that with these great works of fiction, knowing the ending is going to ruin them.”

No one watches a romantic comedy truly wondering if the couple will be happy in the end. With a detective story, you can safely assume the detective will eventually solve the case.

“The point is, really we're not watching these things for the ending,” said Christenfeld. “I point out to the skeptics, people watch these movies more than once happily, and often with increasing pleasure.”

The plot thickens

In a follow-up study, Christenfeld’s team tried tried a variation on the original experiment to identify how and when spoilers work to enhance creative works.

This time, instead of letting readers finish the story, Christenfeld’s team stopped people before they reached the spoiled ending and asked them how much they were enjoying the piece. If the benefit of spoilers comes from simply knowing the ending, you wouldn’t expect to see any increased enjoyment in the middle of a yarn.

Once again, there was a surprise twist.

“It turns out even halfway through a story, you enjoy a spoiled story more, before you get to that spoiled ending,” said Christenfeld.

To Christenfeld, this suggests that spoilers help you know the purpose of the overall narrative, so you’re able to better incorporate all of the details and plot points that get you to the end.

Christenfeld harkens back to “The Usual Suspects,” in which Kevin Spacey is secretly Keyser Söze.

“If you know the ending as you watch it, you can understand what the filmmaker is doing. You get to see this broader view, and essentially understand the story more fluently,” explained Christenfeld. “There's lots of evidence that sort of this fluent processing of information is pleasurable; that is, some familiarity with a work of art enables you to enjoy it more.”

In yet another experiment, the researchers added the spoiler directly into the works.

“We actually modified these stories a little bit – a little bit of hubris going in and ‘fixing’ what John Updike wrote. And it turns out we didn't make them better.”

Extra knowledge about a work of art makes it more enjoyable; when a spoiler is worked into the story itself, it simply makes for a flawed tale.

Does the plot spoil the beauty?

If spoiling key plot points improves a story, perhaps the plot itself is simply a distraction that keeps us from enjoying the rest of it – the sensory descriptions, the character development, the satire, the artistry. Spoilers clear away the need to think about the plot and allow you to enjoy the rest of the story more.

Knowing that Kevin Spacey is Keyser Söze lets you enjoy the clever construction of “The Usual Suspects” and appreciate how the director and the screenwriter manipulate the viewer and drop subtle hints along the way.

“If you're driving up Highway 1 through Big Sur, and you know the road really well, you can now peek around and admire the view, the otters frolicking in the surf,” said Christenfeld.

But if it’s your first time on the road, you have to focus on the twists and turns.

“The plot is in some ways like a coat hanger, displaying a garment,” said Christenfeld. “If it's just a crumpled heap of fabric on the floor, you couldn't admire the garment. A plot is just the structure that lets you do the interesting narrative components – maybe even knowing the ending is useful because it allows you to focus on these other parts, or to understand how it's unfolding.”

Will this finding make people rush out and look for spoilers? Almost certainly not. Despite the fact that most people have experienced a spoiler enhancing their enjoyment of a story, the vast majority of people still think that spoilers ruin stories in some way.

In part, this is due to the fact that we can’t experience a story for the first time twice – we can’t compare the experiences of watching a spoiled and an unspoiled movie, and there’s only one chance to watch an unspoiled film.

In other words, you can only discover once that Kevin Spacey is actually Keyser Söze.