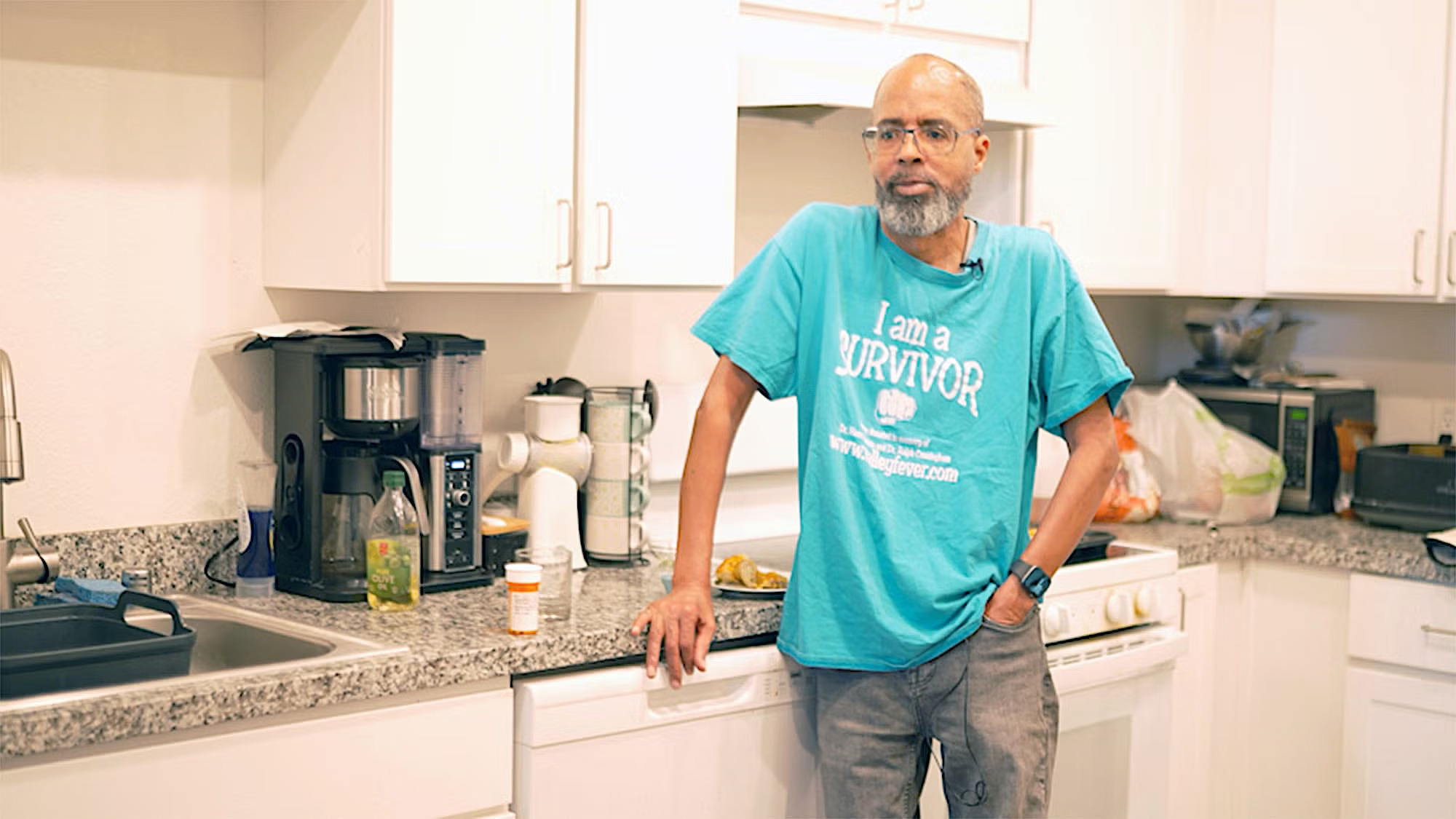

In the den of his small apartment in Stockton, 56-year-old Rex Dangerfield sits at a table. The walls are bare, and the space stripped down to essentials. The T-shirt he wears, stamped with the words “I am a Survivor,” drapes loosely over his narrow frame. When he walks to his kitchen, his steps can be uncertain.

Years ago, a soilborne fungus made its way into his lungs, then into his brain.

“I was helping my mother-in-law re-garden her backyard,” he recalled of a warm spring day in Patterson in 2013. Within two weeks, headaches began. Doctors first blamed migraines. In 2015, he collapsed at work, spiraled into delirium and landed in a hospital bed. The diagnosis was the most feared form of valley fever: meningitis. It can be fatal without lifelong treatment.

“I don’t feel normal anymore,” Dangerfield said through tears. “I used to be able to play basketball. I used to love to bowl. I can’t do that anymore.”

Valley fever, or coccidioidomycosis, is caused by a fungus that thrives in the soil of California’s Central Valley and other arid parts of the West. Churning up the ground can release its tiny spores into the air where they can be inhaled.

The more frequently someone is exposed to dust, the higher their risk. Agricultural workers and construction workers are especially susceptible as are firefighters who dig fire breaks.

Many who inhale the spores may never fall ill. Others, like Dangerfield, are left with devastating disease. That unpredictability, combined with how differently valley fever strikes patients, makes it insidious and hard to diagnose. The disease can be medically treated but has no known cure.

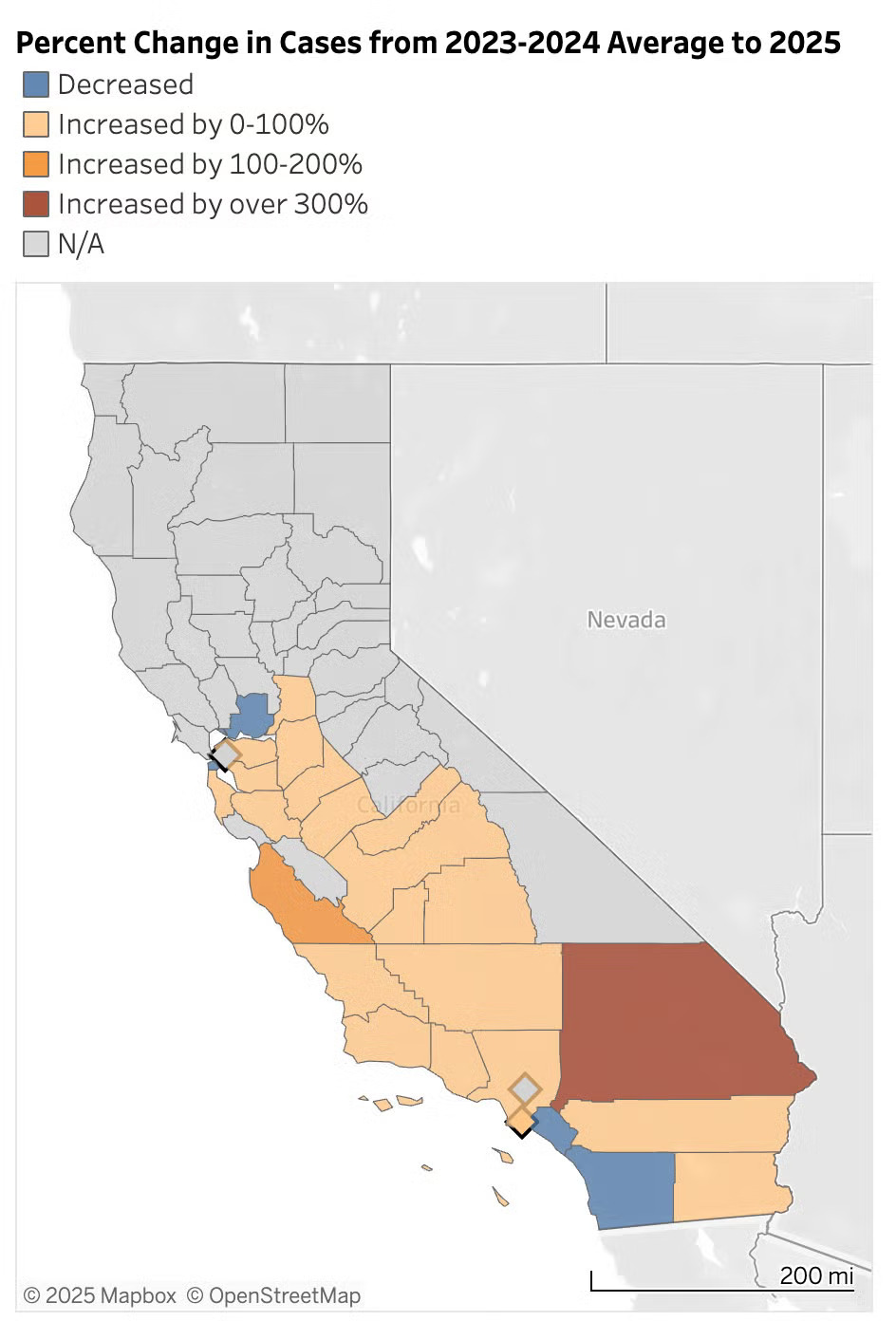

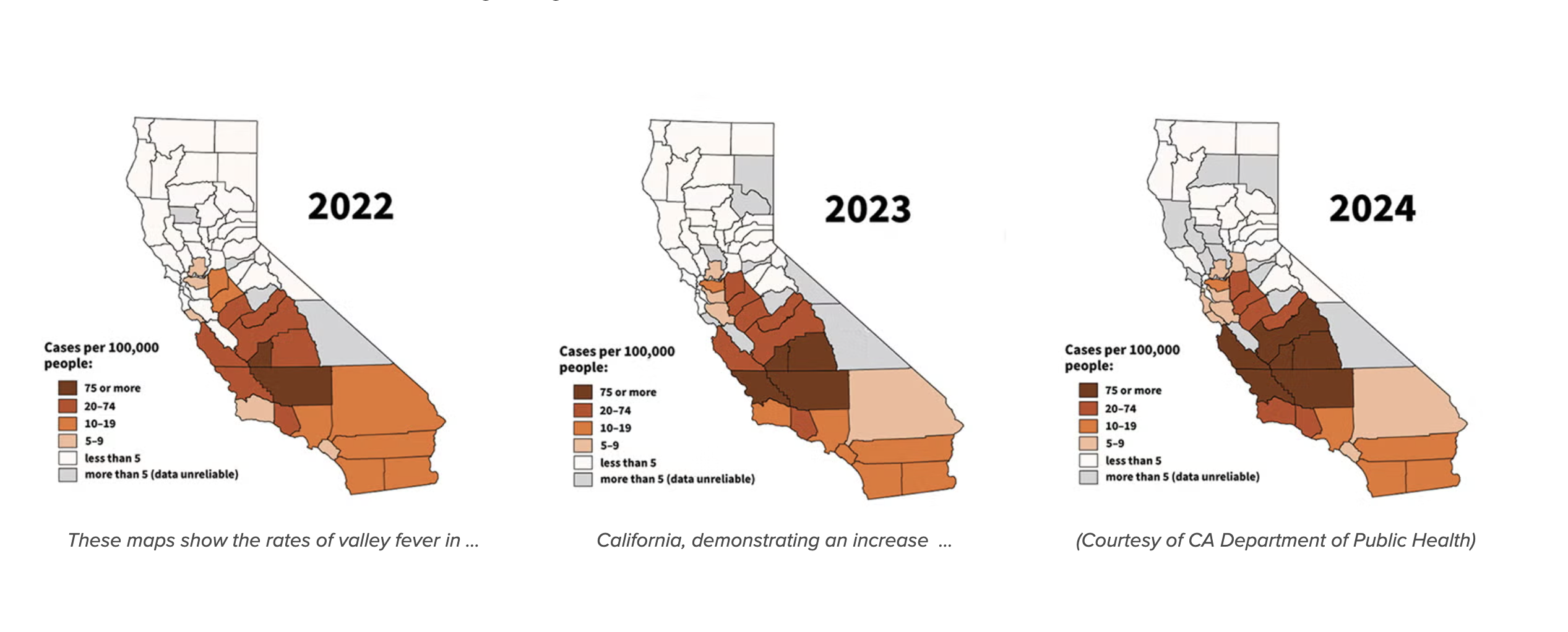

The fungus also doesn’t seem to care what lungs it enters. It’s common in animals, especially among dogs that like to dig. Valley fever cases continue to rise in California and other states. California had a record year in 2024, reporting nearly 12,500 cases. In the first six months of this year, 5,500 people have been infected. Arizona saw its highest caseload in 13 years in 2024.

Their local veterinarian referred them to the UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital. The Rios family drove Cooper four hours through the night to get there.

“It was absolutely terrifying,” Rosemary recalled. “We really didn’t know what we were going in for, but we knew we were willing to do whatever we could to help him.”

The diagnosis: valley fever. Fluid from infection pooled in Cooper’s belly. But veterinary cardiologists suspected the fluid was related to the sac around his heart.

“The pericardium was markedly thickened,” said Dr. Glynn Woods, who became Cooper’s main veterinarian. “It was almost as thick as my thumb, when it should be cells thick just to gently coat the heart.”

Surgeons gently cut a hole in the pericardium to relieve the pressure. It saved him, but the fight was just beginning.

“We were so chuffed he came through the surgery well, then we realized now is the long game,” Woods said. The dog still had to fight the fungal infection, which was sapping his energy. It would mean numerous antifungal treatments. Cooper lost 15 of his 68 pounds and wasn’t gaining it back.

Rosemary learned to drain fluid from ports surgically placed in his chest. That allowed him to get better at home. It bought them time. Cooper kept fighting.

How dogs help track valley fever spread in humans

The severity of Cooper’s valley fever is rare, but Sykes has seen many of those exceptional cases at the UC Davis Veterinary Medicine Teaching Hospital. She also works with researchers at the Center for Valley Fever at UC Davis Health.

For researchers, dogs like Cooper are not only patients but also bellwethers of where the fungus is heading.

“There are lots of dogs, and they don’t travel as much as people,” Sykes said. “They dig in soil, which puts them at risk of the disease. They’re potentially good sentinels or signs that humans might also be getting infected in a region.”

To understand the scale, she and colleagues analyzed nearly a decade of dog antibody tests from around the country. Not only did cases increase in that time, nearly 38% of the test results were positive. She then worked with colleagues at UC Berkeley to map the dog cases in relation to human cases. No other animals are tracked by public health agencies.

“We were holding our breath thinking, ‘What is this going to look like?’” Sykes said. “The maps were just perfect in terms of what we know about the distribution of the fungus in people.”

In California and Arizona, where human cases are well tracked, the overlap was striking. More surprising, positive dog cases were turning up in states where valley fever is not considered endemic. It also provided insight to its spread in states that aren’t required to report human cases.

“We were given this window into what might be going on in these states,” Sykes said, “because now we could see it in Texas, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Washington and Colorado as well.”

It’s a sign that the fungus may already be affecting people in those states without being recognized.

Climate change fuels the spread of valley fever fungus

For decades, valley fever was considered a disease of the Southwest. But climate change is fueling the perfect conditions for the fungus to grow — heavy rains followed by drought and wind. Thompson said he’s seen cases as far away as Nebraska.

“We think it’s probably already in some of these Midwest states,” Thompson said, “just not diagnosed.”

He co-authored a paper estimating that 206,000 to 360,000 people in the United States developed symptomatic valley fever in 2019 — up to 18 times more than the cases that are reported through national surveillance.

Thompson’s research also shows that the fungi can hitch a ride on tiny particles found in wildfire smoke. Fires can produce strong updrafts that send fungal spores aloft and traveling thousands of miles.

New valley fever treatments and vaccines offer hope

Antifungal drugs can suppress valley fever but not cure it. Some patients require them for life. Doctors at the Center for Valley Fever at UC Davis Health focus on early, accurate diagnosis and manage the most severe cases.

New medications are on the horizon, said Thompson. Two drugs in development have shown promise against fungal pathogens with no current treatment, and both work well against valley fever.

Research collaborations are pushing ahead on other fronts. Blood samples from patients like Cooyar and Dangerfield are sent to labs in Texas, UCLA and UC San Diego to aid vaccine and genetic studies. Scientists are studying whether certain immune genes could play a role in why some people have such severe illness, while others show few, if any, symptoms.

On the veterinary side, Sykes hopes that dogs might also help scientists understand the disease in humans. She’s looking for genetic factors that make some dogs more vulnerable to valley fever. Lower genetic diversity in dogs could make those clues easier to find.

A preventive vaccine for dogs is in development and could be approved in the coming years. That offers hope for a human vaccine as well.

“We’re really at the pinnacle of science right now,” Thompson said. “We’re hoping to see some big breakthroughs and advances just over the next six months.”