Jason Pohl, UC Berkeley

In just a few years, AI has gone from a tech novelty to a society-altering force. It has revolutionized scientific research, classrooms and workplaces. People around the planet have turned to it to break through writer’s block and to contest parking tickets.

But that growth has not come without risks. The economy is increasingly propped up by bets about the technology’s future — 80% of U.S. stock gains last year came from AI companies. Policy battles are ramping up as some seek to rein in tech companies and others opt for an unregulated Wild West. Deepfake and explicit videos are causing harm and blurring what is real in an already fragmented information environment.

As a global leader in the development of AI technology as well as research into the ethics, policies and practices around its use, UC Berkeley’s experts are at the forefront of this rapidly changing technology. Below, UC Berkeley News asked some of the campus’s leading AI experts to summarize in 100 words — and in a short phrase — the developments they’ll be monitoring in 2026.

‘Will the AI bubble burst?’

Stuart Russell

Current and planned spending on data centers represents the largest technology project in history. Yet many observers describe a bubble that is about to burst: revenues are underwhelming, the performance of large language models seems to have plateaued, and there are clear theoretical limits on their ability to learn straightforward concepts efficiently.

If the bubble bursts, the economic damage will be severe. But for the bubble not to burst, breakthroughs will need to happen that take us close to artificial general intelligence. AI developers have no cogent proposal for how to control such systems, leading to risks far greater than economic damage.

— Stuart Russell, professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences

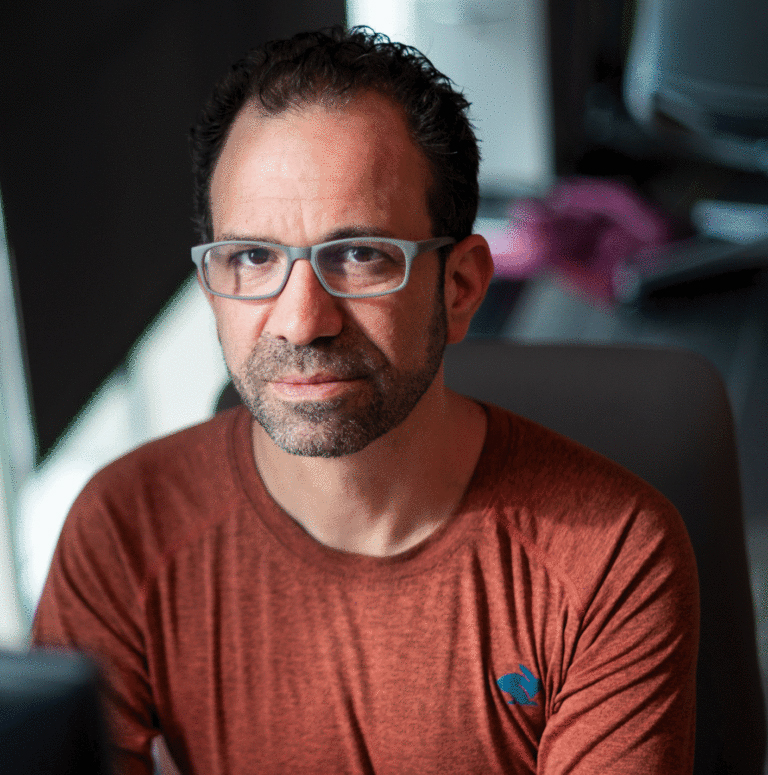

‘Can we trust anything anymore?’

Hany Farid

I will be watching the accelerating erosion of trust driven by increasingly convincing AI-generated media. In 2026, deepfakes will no longer be novel; they will be routine, scalable, and cheap, blurring the line between the real and the fake. This has profound implications for journalism, democracies, economies, courts and personal reputation.

I am especially concerned about the asymmetry: It takes little effort to create a fake, but enormous effort to debunk it after it spreads. How society adapts — technically, legally and culturally — to a world where seeing is no longer believing will be critical.

— Hany Farid, professor of information

‘AI-enabled discoveries that benefit people’

Jennifer Chayes

Major technology paradigm shifts like AI come with significant benefits and risks, and I expect AI will become ever more part of our daily lives in 2026.

Individuals and industries are finding exciting new uses for personalized agents and related technologies. For example, AI accelerates scientific discovery in ways that were previously unimaginable.

Conversations about the responsible and ethical use of AI should be prioritized across sectors and civil society. We must work collaboratively to mitigate AI’s potential harms and find inclusive ways to empower people.

Our challenge is to apply AI to advance knowledge, expand understanding and benefit humanity.

— Jennifer Chayes, dean of the UC Berkeley College of Computing, Data Science, and Society

‘Privacy risks created by chatbot logs’

Deirdre Mulligan

People use AI chatbots for emotional support, spiritual guidance, relationship counseling, legal advice and intimacy, and they turn over reams of information about their follies, fantasies and fears.

Adam Raine’s ChatGPT logs cataloging struggles before his death by suicide are central to his family’s lawsuit. While Adam’s chats are being used to address harms, users’ logs risk disclosure in more troubling settings. A recent court order directed OpenAI to save all chats for a copyright lawsuit, and the Department of Homeland Security successfully demanded a user’s prompts.

Expect more demands on AI companies for personal data and lawsuits challenging how they collect and use it.

— Deirdre Mulligan, professor of information

‘Relationship chatbots worsen human isolation’

Jodi Halpern

This year will see the expansion of companion chatbots to young children. Already, one-third of teens prefer talking about their feelings with bots instead of people. Using the existing social media business model, companies manipulate and incentivize overuse. Sadly, teen dependence is associated with suicide. Yet “buddies” for toddlers are an emerging market without guardrails.

In the short term, we need regulation until safety is established. Long-term, how will toddlers who learn “empathy” from sycophantic bots rather than people develop the mutual empathic curiosity crucial for successful relationships? How will they participate in democracy with people who have different perspectives?

— Jodi Halpern, professor of public health

‘Whether robots can learn useful manipulation tasks’

Ken Goldberg

I’m very concerned about widespread claims that humanoid robots will “soon” replace human workers. Significant advances are being made, but robots have nowhere near the dexterity of kitchen workers, car mechanics or construction workers.

There is a vast gap between the amount of data available for training large language models such as ChatGPT and the amount of data available to train robots. Researchers around the world, including my own lab, are working on this, and I’m watching for breakthroughs in how to close this data gap.

— Ken Goldberg, professor of engineering

‘Progress on worker technology rights’

Annette Bernhardt

In 2025, unions and other worker advocates began to develop a portfolio of policies to regulate employers’ growing use of AI and other digital technologies — an area where workers currently have few rights.

This year I will be watching for progress in legislation to establish guardrails around electronic monitoring and algorithmic management, addressing harms such as automated firing, discrimination, invasive surveillance and profiling of union organizers.

Equally important will be the success of bills requiring that humans have a meaningful role in critical decisions that affect our lives (like health care), which is protective of both workers and the public.

— Annette Bernhardt, director of the UC Berkeley Labor Center’s Technology and Work Program

‘Weaponization of AI against workers’

Nicole Holliday

My research focuses on AI that aims to evaluate how people speak. Programs like the Zoom Revenue Accelerator and Read AI are being used by companies, often without worker knowledge or consent, to rate employees.

These systems rate speech on parameters like “charisma,” but because they are black-box algorithms, no one knows how they work. They are trained on “idealized” speech, so they show systematic bias against neurodivergent speakers, second-language English speakers, and anyone who speaks a stigmatized dialect. I’m watching to see how systems are weaponized against workers and how the courts deal with these patterns of bias.

— Nicole Holliday, associate professor of linguistics

‘AI’s effect on political conflict’

Jonathan Stray

The lack of good definitions and evaluations of “politically neutral AI” is a problem for democracy. The White House recently issued an executive order requiring “politically neutral and unbiased” AI for federal contractors. They didn’t provide a definition.

We recently saw Grok turn into “MechaHitler.” Next time the change could be more subtle and we might never detect the bias. With any luck this year will see advances in defining and implementing “politically neutral” AI. What does this idea even mean? Should an AI ever persuade you? And how would we build models that have this property?

— Jonathan Stray, senior scientist at the UC Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible AI

‘More sophisticated deepfakes’

Camille Crittenden

This year will mark when video and audio manipulation goes mainstream. Deepfakes have proliferated across social media — from whimsical images of beavers piloting planes or the pope in a puffy coat to harmful uses, including child sexual abuse material, political disinformation and financial fraud.

What changes in 2026 is scale: Powerful tools and platforms are making sophisticated audio and video manipulation cheap, fast and accessible. New California regulations requiring proof of content authenticity are an important step toward restoring trust but will not be sufficient. Users will need stronger media literacy to navigate an environment where seeing and hearing are no longer believing.

— Camille Crittenden, executive director, CITRIS and the Banatao Institute

‘Intelligence limits and the search for truth’

Alison Gopnik

I’m expecting that, in spite of the commercial pressures, we will realize that there is no such thing as general intelligence, artificial or natural. At the same time we may see progress toward more realistic models that engage and experiment with the external world, in the way that children do.

My guess is that intrinsically motivated reinforcement learning systems — where the reward is finding the truth rather than getting a good score from humans — may make real progress in this regard.

— Alison Gopnik, professor of psychology