Aylin Woodward, UC Santa Cruz

“The Cherokee learned that if you ask a question and you are patient, after seven days it will answer itself.”

The penultimate line from the first ever animation in the Cherokee language — named “The Beginning They Told,” or ᏗᏓᎴᏂᏍᎬ ᎤᏂᏃᎮᏓ — shares both a story and a lesson, as Grandpa Beaver, Little Water Beetle, and the Great Buzzard Su Li work together to form the Appalachian and Rocky Mountains.

Upon the video’s success, more than 20 years ago, the director and creator, Joseph Erb, turned down an invitation to be an Ivy League educator. “I wanted to go home and teach my community how to tell stories through animation,” said the 51-year-old Cherokee animator.

His legacy of teaching is now two decades strong, and in 2022 he joined the UC Santa Cruz film and digital media department. As an associate professor, he is a pivotal part of a growing Indigenous studies community, an educator prioritizing intersectional approaches to filmmaking, and an artist whose work leaves the classroom, with animations, sculptures, and illustrations on display at galleries, installations and film festivals across the country.

Communicating across platforms

After completing his Masters of Fine Arts degree from the University of Pennsylvania, where his mentor offered him a teaching position, Erb returned home to Oklahoma in 2002. There, he began teaching youth programs including Cherokee and Muscogee Creek students from kindergarten to high school not only how to create videos and do animation, but how to document and tell Indigenous stories.

With only one computer shared among the entire class, teaching computer animation wasn’t feasible at the time, Erb said. “So I started doing stop motion animation with the kids.”

Erb asked his students to bring story ideas to the class to share, then they would decide as a group which ones they would bring to life. “As a result of that, everyone started sharing Cherokee stories with each other,” he said.

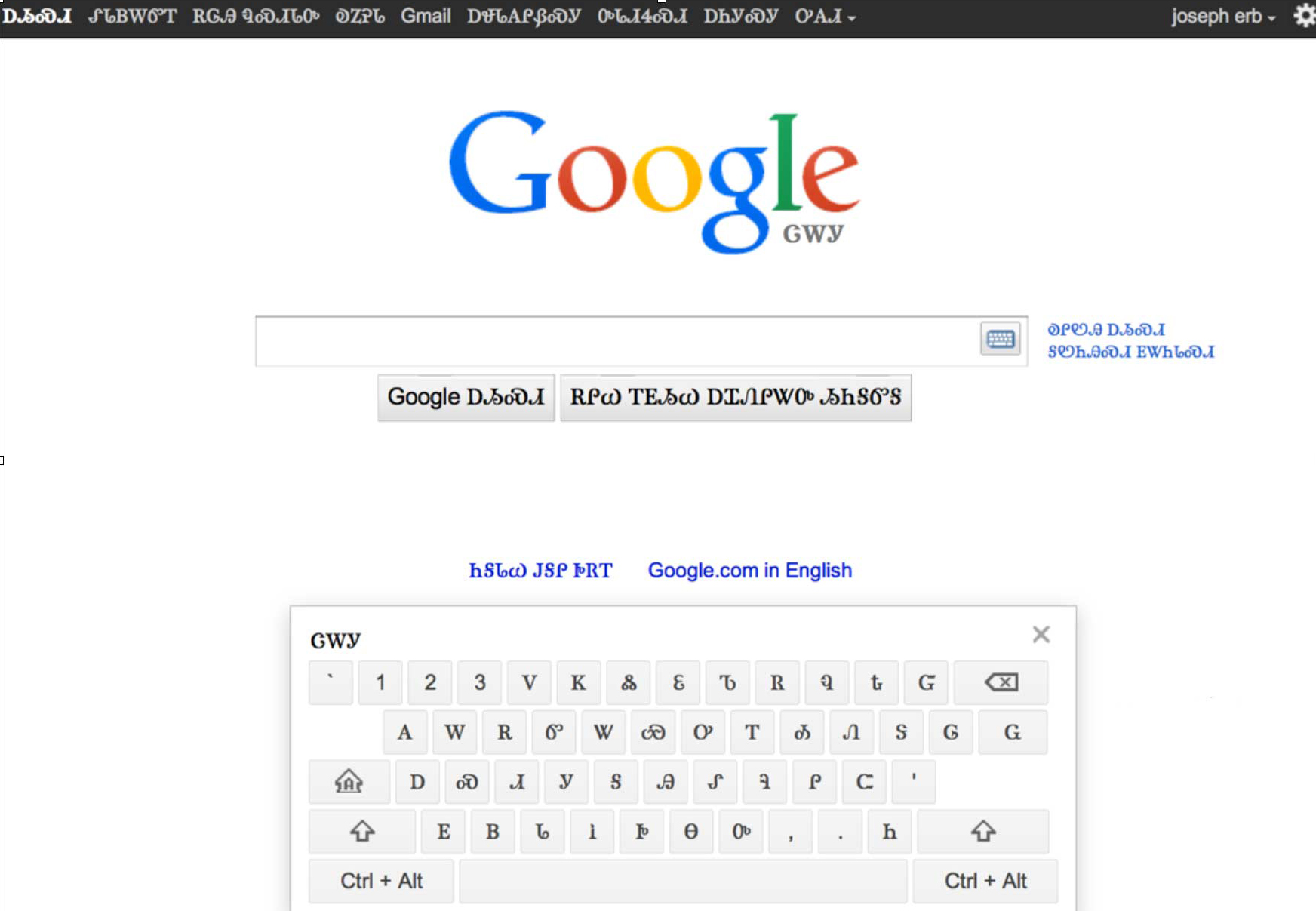

In the late 2000s, Erb took the lead on efforts to include Tsalagi, the language of the Cherokee nation — one of the largest tribal nations in the country — included on Apple platforms, including the iPhone, Windows, Google and Microsoft.

“We were initially rejected by Microsoft for not having enough speakers of the language,” Erb said. “So we went to talk to Apple around the end of 2007.”

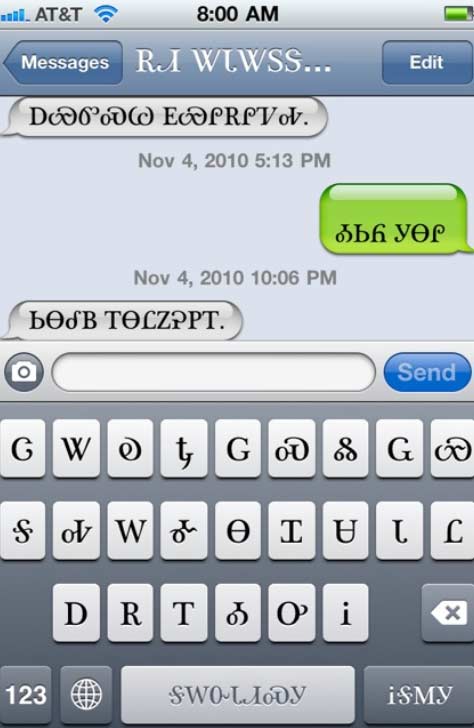

An iPhone screen in the Cherokee language

He liaised a meeting between company heads — “everyone but Steve Jobs” — and the chief of the Cherokee tribe at the time, immersion teachers, translators and kids in his program. The meeting was successful, and the Cherokee language became part of the OS 4.1 release on the iPhone in 2010 — the first Indigenous language supported on Apple devices.

“Then Google contacted us, and we started adding our language to the Google search engine and Gmail. And then Microsoft invited us back and we got on Windows 8 and Windows 10,” he said. “It was a lot of work. Teams of people, many of them volunteers in the community, spent thousands of hours to do a million and a half translations.”

Erb later helped other Indigenous nations, like the Osage, follow suit. The Cherokee people have always been quick to adapt to new technologies, he said; they had the first Native printing press, for example.

His language in technology work aside, he is a prolific sculptor, jeweler and artist.

Erb—called “Doda,” meaning father, by his young son—illustrates children’s stories that he collaborates on with other Cherokee artists, like “Clack, Clack! Smack!” a narrative about the Indigenous sport stickball, which resembles lacrosse.

He also enjoys working with copper. One of his pieces, which he worked on while teaching at the University of Missouri prior to moving to Santa Cruz, is on display at the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma.

Called “Indigenous Brilliance,” the two-story digital illustration rendered on copper panels is meant to encapsulate Native knowledge, resilience, and the affirmation of a vibrant future for his people. The museum honored Erb with a “Creative Native” award for the work at its annual Tribal Nations gala in 2022.

Cross-cultural compassion and learning

Joseph Erb (left) and John Brown Childs; credit Guillermo Delgado-P.

Erb is frustrated that Indigenous culture is often depicted in the media as past tense, despite the fact that Indigenous peoples and nations are very much contemporary and part of the future, he said. Many of his goals in the UCSC film department center around bucking this theme and demonstrating that every member of his community matters to that vision of the future.

“He’s a model for positive interaction,” said John Brown Childs, a member of the Massachusett tribe and distinguished emeritus professor of sociology at UCSC. “It’s not just what he says, it’s what he does, his words and deeds. And the students really get that, and the colleagues who know him — we all love him, he’s very generous with the sharing of his knowledge and expertise,” Childs said.

He has been friends with Erb and his family for several years. The two met when Erb first settled into faculty housing on campus in 2022, next door to Childs and his wife, who now call him “Netop,” a term of deep friendship in the Massachusett language.

The two, both part of the Indigenous faculty network, enjoyed discussing tribal values and how to embrace the world while remaining true to those values.

“Joseph is very notable for being deeply rooted in his belonging to and support for the Cherokee Nation,” Childs said. “At the same time, he’s also able to reach out to other communities to be a help to them.”

Erb helped Childs’s tribe work on a language revitalization program, assisting the Massachusett tribal language committee.

“It speaks well of the university that he is here,” Childs said. “He’s an example of the right way to go about hiring.”

The addition of Erb to the UCSC community came at a time when school leadership began recognizing the campus had amassed a strong cluster of faculty and students focused on Indigenous studies and wanted to continue growing those offerings, according to Celine Parreñas Shimizu, former Dean of the Arts.

She recalled being struck by Erb’s underlying mission, which he shared after their first meeting: “He said, ‘I don’t do my research for myself. I do it for the Cherokee people.’”

“He redefines how we think of the role of scholarship in society — it’s really to serve community, and his media reflects a living thriving culture of people who’ve never vanished,” she said.

Stories, Erb said, push his communities forward so that they continue to be pertinent and survive. He feels that Parreñas Shimizu — and the entire department — are fully supportive of his values as an educator.

“She understands that when you bring in multiple perspectives of how you create film, you make better filmmakers, no matter who they are, or what culture they come from,” Erb said. For instance, he said, a Mexican filmmaker who learns from a Japanese filmmaker, can learn an entirely new way of thinking about how films are made — about their structure and form.

“This is the kind of environment UCSC has. It has a high percentage of multicultural racial groups that are here,” Erb said. “Throughout my department, there’s a lot of work that goes into making gorgeous media about places around the world that you haven’t heard of or you haven’t thought about, and are dealing with issues that affect them, from land back movements to environmental movements.”

The university enables artists to talk about these big ideas without trying to homogenize anything, Erb and Parreñas Shimizu agreed.

“We cannot but be moved by the way students wish to learn, and they’re asking for a decolonized curriculum. Native American cinema, African American cinema; I think that’s what they consider a more complete education that fills the glaring gaps in their knowledge,” Parreñas Shimizu said, adding that because of this desire, students seek out Erb and UC Santa Cruz specifically.

An accessible future

UC Santa Cruz has long been lauded as a hub in language and AI work. Matthew Wagers, professor and department chair of the linguistics department, is leading an effort to establish a cross-campus research network focused on diversity in language technology, including AI large language models, across six of the UC campuses.

With such models, which undergird programs like ChatGPT, the demographics of speakers whose languages and speaking patterns help train the algorithms can entrench certain biases and patterns, he said. Through workshops, as well as online resources for training and curriculum, the goal of the project is to highlight and address the need for diversity in the design of language technologies, while identifying and expanding the impact of the UC system’s contributions on these areas.

Wagers said he and his colleagues are trying to broaden the reach of their research, so those training these models, for instance, include the languages of the adults and children that reflect the community.

“Study participants are often monolingual, and California is, of course, a multilingual, multi-ethnic kind of place, so what we’re learning from those speakers might not always be representative,” Wagers said.

The project, which began earlier this year, will end in fall 2026.

For nearly two decades, Wagers has studied language processing — how people access the meaning of words and put them together. He views this UC-system-wide effort as an opportunity to connect a network of research across California to explore how humans interact with AI, and the challenges therein that remain unaddressed.

“There are opportunities to improve language technologies to address the needs of people who speak or communicate differently, such as people who stutter, or language users who are blind,” Wagers said. “There has been a long tradition of linguists and language activists at UCSC looking to expand access to language tools.”

Wagers said Erb’s work getting the Cherokee language onto phones, computers and platforms like Google is demonstrative of how to generate such access in an impactful way.

“We live our lives online and through technology now, and if we simultaneously want to live our lives in the language of our community or of our family and heritage, there has to be an effort to bridge this gap,” Wagers said. “Even having the right kind of keyboard so that you can type in that language helps a diverse group be their full and authentic selves.”

That task was far from easy, Erb said.

The Cherokee language has 86 characters, which affected the design of a digital keyboard across platforms optimized for languages like English, with around one-third as many characters. Rather than an alphabet, Cherokee uses a writing system where each symbol represents a syllable.

“It couldn’t take up the whole screen and we had to follow Apple’s philosophy about design without quite knowing what that was,” Erb said. “Then sometimes we had to come up with words. Like, we didn’t have a word for email.”

A future goal is addressing voice-to-text in Cherokee, he said. Cherokee is a tonal language, meaning changes in tone can alter the meaning of words, so that makes the task quite complicated.

Reflecting back on the quarter-century journey that brought him to UC Santa Cruz, Erb is hopeful about the impacts he’s had.

“Our language is still in decline, but we have more tools than we used to when I started,” he said. “The tech companies now take us seriously. When I first started reaching out, we weren’t even a thought.”

His day-to-day work has become more joyful, too. A lot of the difficult, repetitive work involving coding for operating systems or typing up Cherokee documents are behind him, he said. “Now, instead of doing that stuff, we’re sitting there making stories about our community.”

Erb recalled having to draw each Cherokee word by hand in Photoshop 20 years ago for “The Beginning They Told.” Largely thanks to his work since then, that process is no longer necessary.

“Today, our filmmakers and bookmakers and writers can type in our language,” he said. “It ultimately preserves the inherent, important knowledge therein.”