Robyn Schelenz, UC Newsroom

The University of California has always focused on bringing the fruits of its scientific research out of the lab and into the real world, but rarely has it had better ambassadors for its efforts than those in 4-H, the UC-administered youth development program known by its iconic four-leaf clover.

Since 1914, UC and other land-grant universities around the country have run statewide 4-H programs that engage youth in community activities, particularly those relating to agriculture, livestock and food. Since its earliest days, kids aged 5 to 18 have come to 4-H to have fun, learn new skills and then pass on that knowledge to peers and adults alike. Service and leadership are integral to the 4-H experience, which is why it’s no surprise the program’s alumni continue to make an impact in so many California communities today.

Tracy Schohr: Drawing on 4-H to tackle real-world problems

When Tracy Schohr describes her career as a UC Cooperative Extension advisor, it’s clear that she wears many hats: working alongside ranchers in Plumas, Sierra and Butte counties to address issues ranging from wildfire to wolf predation; organizing community events; testifying in front of Congress about agricultural workforce needs; and occasionally even sitting down in front of a desk. It’s a career so busy and wide-ranging it might make Indiana Jones grateful that he only wears a single fedora. She traces the origins of her successful and interesting career to 4-H.

“Everything you do in 4-H has some element of a team putting together an activity, or a fundraiser,” Schohr says. “You learn about agriculture and the community you live in, but you also have leadership opportunities, like planning community service or leading a meeting using parliamentary procedure from a very young age.”

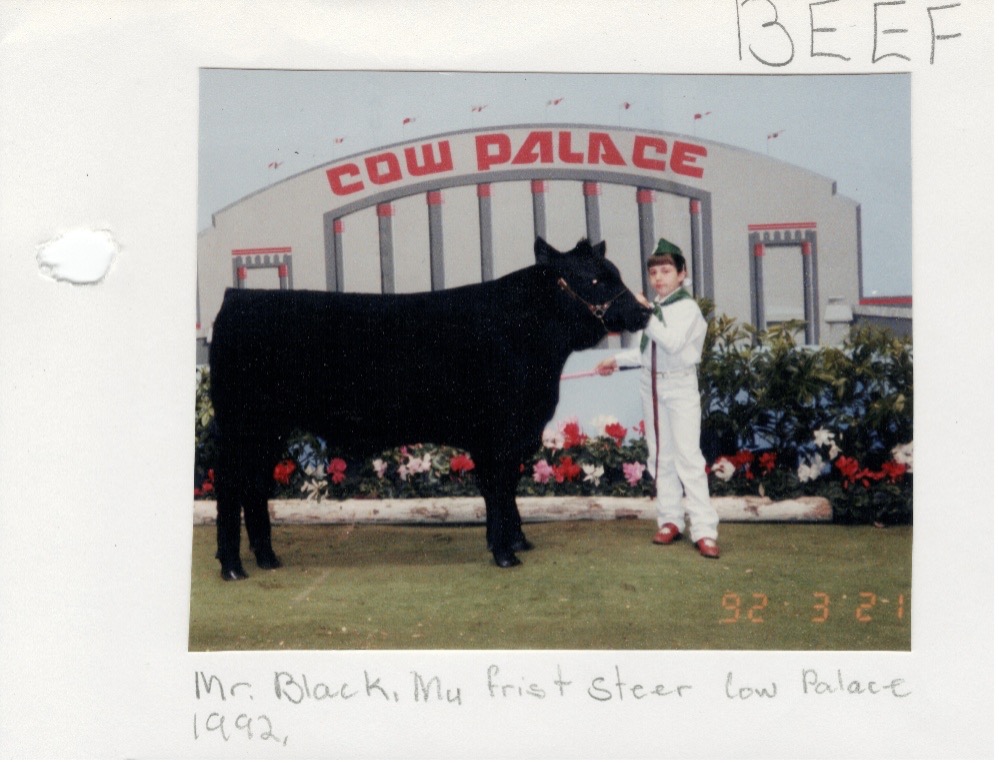

Schohr embraced every opportunity 4-H gave her, from cooking and photography groups to raising livestock and learning to ski. Showing cattle in Butte County as part of 4-H allowed her to not only to learn about genetics and provide local meat for the community, but to understand from a broader point of view the challenges and issues faced by livestock producers — including those of her own family, whose Northern California ranch has been raising cattle and growing rice for more than a century in Gridley.

When it came time for college, Schohr embraced it with the same zeal, earning a business degree in agriculture at California State University, Chico, then a rangeland-focused master’s degree in horticulture and agronomy at UC Davis. Schohr loves the people in agriculture and doing the research on the ground with farmers and ranchers that helps them be sustainable and profitable. UC Cooperative Extension gives her that opportunity. Part of UC’s statewide division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Cooperative Extension oversees California’s 4-H program and also provides a huge array of other programs and services to ranchers, farmers and land managers.

Tracy Schohr remains active around 4-H, here volunteering as a judge for the round robin competition at the Plumas-Sierra County Fair.

“Cooperative Extension takes the science and knowledge that is developed at the university and puts it in the hands of the people on the ground,” Schohr says. “And it’s not just research from the University of California, we're pulling in research from all across the nation to help land managers, farmers, and ranchers in California address the challenges they face, while conducting research in our own local communities, too.”

UC’s Cooperative Extension program provides science-based support in all 58 California counties, with 189 advisors, 104 specialists and 350 community educators on the ground. It’s part of UC’s public service mission and has helped make California the nation’s leading agricultural state, with a record-breaking $61.2B in revenue in 2024. Aiding that prosperity through long-term research and outreach are part of Schohr’s portfolio, but when a new crisis emerges, Schohr also responds.

These days, that means working as an intermediary between ranchers and state wildlife officials to address the return of gray wolves in Northern California. Eighty years after the last sighting of a wolf in California, a gray wolf tracked from Oregon took up residence in the state in 2011. Now there are 10 wolf packs, a remarkable story of recovery that also presents serious challenges to ranchers as they grapple with significant cattle losses and search for ways to co-exist. As a livestock and natural resources advisor, Schohr is on the front lines of the conflict, acting as a bridge between the many people impacted by the arrival of the wolves in California.

“When the first wolf was in the Sierra Valley, I was called by the Department of Fish and Wildlife to connect with the rancher where the wolf’s GPS collar was pinging,” Schohr says. Much of her focus shifted to working on every side of the issue, from analysis of cattle killed by predators to providing economic and social support for ranchers and the community. It’s an issue that takes a village: county sheriff, county supervisor, local cattleman’s group, forest and wildlife agencies.

Schohr and colleagues are trying various solutions: From patrolling on horseback to using artificial intelligence to analyze wolf patterns captured by game cameras. Schohr recently delivered wolf scat and DNA swabs from wolf predations of cattle to UC Davis for analysis that could help ranchers and scientists alike understand which wolves are learning to feed on cattle and further inform their response.

More alarming even than wolves is the growing threat of wildfire, which has ravaged large swaths of Northern California rangelands in recent years. During the 2021 Dixie Fire, one of the largest wildfires in California history, Schohr assisted with operations in the incident command center in Chico, Calif. When a rancher asked for help accessing some of his livestock in the fire zone, Schohr connected him with a sheriff’s deputy she figured would be a great fit for the job — they knew each other, and livestock, through 4-H. That’s just one of the ways her childhood network continues to pay off.

“Extension is really about being boundary spanning,” Schohr says. “We can work with different people in different places to try to find that common ground by bringing in economics, natural resources and social sciences, while tying in research and trying to find a solution that can balance all of these challenges that are happening out in the environment.”

When Schohr isn’t building bridges and conducting research she still makes time to help out on the family ranch, bringing the experience of Cooperative Extension to bear. How does she juggle all of it?

“Uh, I question that,” she laughs. “My brother [another 4-H alum] questions that. But going home on the weekend or an evening and being able to work with my brother on a project like water quality or business management, it gives me hands-on experience that I can bring back to helping other producers.”

Ariel Rivers: Spreading the love of 4-H

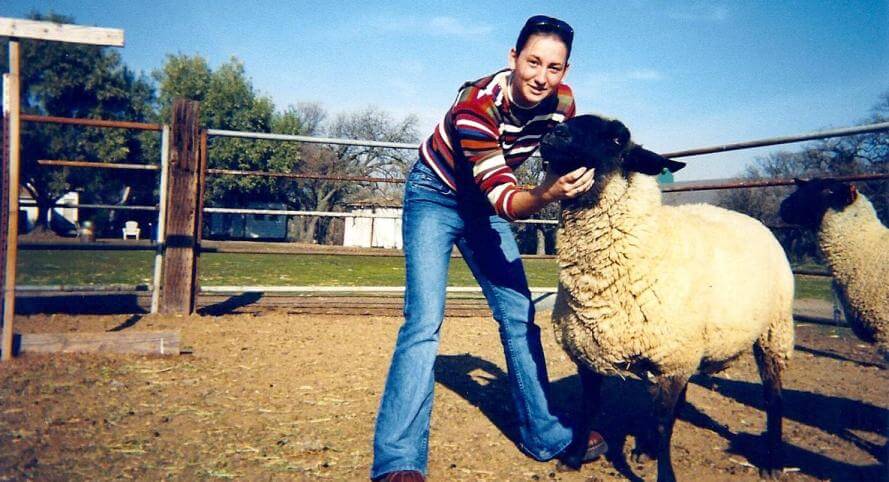

The daughter of ranchers in Livermore, Ariel Rivers didn’t necessarily expect to graduate high school, let alone college. Not that it was top of mind — by 9, she was busy managing her own flock of sheep, thanks to 4-H.

“I felt like I could control them better than a giant steer, you know?” Rivers says. “I basically became a little sheep entrepreneur.”

Like Schohr, Rivers participated in the full range of experiential and learning activities through 4-H, which put her on the road to college (Rivers credits an elementary school teacher who knew her from 4-H in making higher education seem within reach). She developed leadership skills and learned about fundraising, along with breeding and selling her sheep. Local business owners and other community members paid well above market price for her sheep and other 4-H livestock to further support the dreams of young locals.

“I was so obsessed with 4-H that I stayed on as a camp counselor through high school,” Rivers says. “4-H was where I saved up money for college, developed early skills around finding careers and learning more about science, developing skills around public speaking, all of that. It really shaped my entire personality.”

Another major influence on Rivers and other youth in her community was nearby Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which hosted events for girls in STEM, along with “‘Science Saturdays,’ a weekend lecture series for local kids. “It was really fortunate in that I grew up in a community that had that agricultural focus, but also had that science focus, and that increased attention to higher education.”

UC Davis was a natural fit for college, not only because of her passion for farming, but because she wanted to help her parents manage problems on their ranch. “Our property only has a single, unproductive well, and we always ran out of water in the summer, so when I got to college, I was like, ‘there must be some solution to fix this. I love science, so I’ll study hydrology and soils.’”

Rivers went on to earn a Ph.D. from Penn State in entomology and international agriculture and development, expertise that has led to her current role overseeing membership engagement for the National Association of Conservation Districts, a nonpartisan organization that brings together farmers, government agencies and conservation groups to support advocacy, education and partnerships for the nation’s conservation districts, including those in California, where Rivers is based.

“Growing up in the Bay Area, you see millions of people, literally on one side of the hill, and then the other side of the hill, it’s all agricultural land. I realized we need more conversations about what's happening in these different places — there can’t be this dichotomy of urban versus rural.”

In Rivers’ role, she gives a lot of talks to try to bridge that divide and to raise awareness of the wide variety of careers in agriculture and ag sciences.

“For those of us connected to farming or ranching, or who grew up in it, it’s a lifestyle, you’re pretty much guaranteed to be committed to it — but that’s 2% of the population now. So we have a lot of challenges. I work with farmers and ranchers to think about how to improve their operations. And there’s a lot of jobs that just don’t get filled because people don’t know they exist.”

“So how do we raise awareness so more people realize farming is important and can be an interesting and fantastic career?”

If the trajectories of Schohr and Rivers are any indication, the path may well run through 4-H.

Learn more about 4-H and its members and alumni below:

UC Agriculture and Natural Resources: “Where’s the Food?”: A 4-H Journey Beyond Ready

UC Agriculture and Natural Resources: Silver medalist U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Sagen Maddalena reflects on her path from 4-H to Olympics