Robyn Schelenz, UC Newsroom

Purrs of contentment. Soulful eyes locked on yours over dinner. Valentine’s Day?

Not for pet owners. For those of us who share our lives with animals, this is a daily — if not exactly romantic — experience. So are the various barks, meows, whines, and other, sometimes adorable, often insistent, methods of communication our four-legged friends use to express what they want. Or how they feel when we don’t get it.

What if it were possible to better understand our pets? Some pet owners have begun using simple devices — often referred to as soundboards — that purport to help dogs and cats communicate with us by pressing electronic buttons.

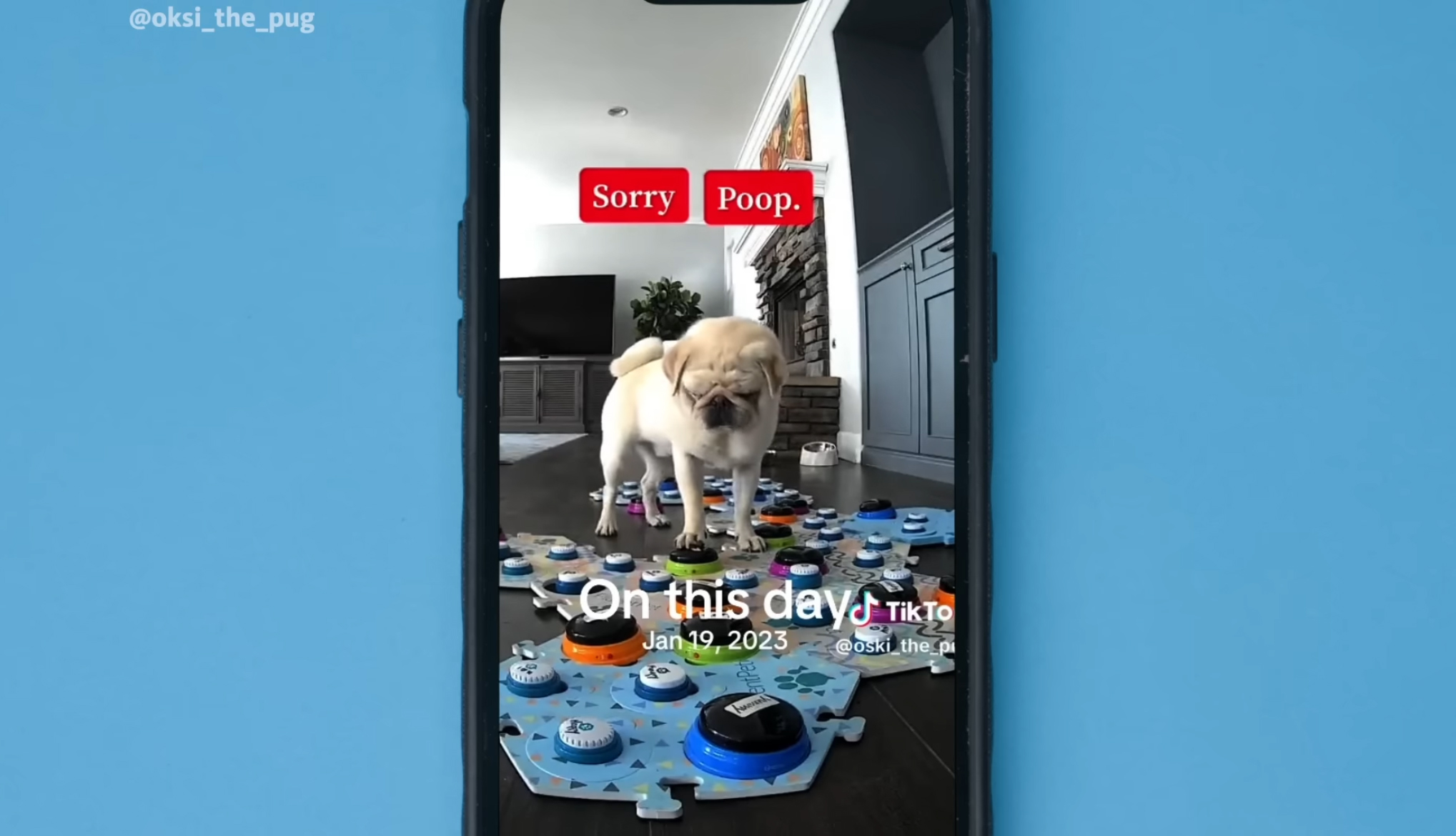

Social media is filled with videos showing dogs, cats and parrots learning the meaning of dozens of buttons and pressing them to “talk” with their people — and a few of these chatty animals have become minor celebrities as they seemingly converse, not just about food and walks, but about more complex concepts like love, strangers and time, opening a window, potentially, into what our pets are thinking.

But do these pets know what they are saying? Or are these videos a hoax? UC San Diego professor of cognitive science and language acquisition expert Federico Rossano had the same questions, and entered the world of TikTok and the complicated history of animal studies to find out.

Social media meets science

Dog buttons first came to Rossano’s attention in 2019, when San Diego-based speech pathologist Christina Hunger started training her dog, Stella, on a soundboard with multiple buttons. Hunger used assistive communication devices designed with similar functionality to help young children acquire language. As she watched her dog develop, she thought Stella, too, might have something to say.

Federico Rossano, associate professor in the department of Cognitive Science at UC San Diego, founder of the Comparative Cognition Lab and leader of the Dog Communication Project.

Stella’s apparent success in learning how to use the board to communicate (she now knows 50+ words and creates sequences as many as five words long) earned the pair media coverage from Good Morning America, CBS and other news outlets. Scientists were skeptical: Had Hunger actually trained her dog to “talk?”

“My colleagues asked me, ‘Would you be interested in doing some research on this?’” Rossano recounts. Previous animal language studies involved training primates to use sign language, but the studies had been largely debunked and were fraught with controversy about animal welfare. “I sent four papers to my colleagues saying, ‘this is why we should not be doing it.’”

A few months later, Rossano received a text from Leo Trottier, a UC San Diego cognitive science alum who had created a company, CleverPet, to provide something akin to a video game experience for dogs at home all day. He was thinking about getting into the soundboard space (note: he did; FluentPet was founded in 2020. Neither it nor any other button company provides compensation for this article or Rossano’s research). Trottier sent Rossano a video of an intriguing pup named Bunny. The way this Old English Sheepdog-Poodle mix, or sheepadoodle, used buttons caught Rossano’s attention.

“Now there are two dogs [Stella and Bunny] that at least seem to be doing something interesting,” Rossano said. “But I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life trying to train one dog to do this.”

Trottier informed him that not two, but at least 500 people were interested in being part of a study. Hearing this during the beginning of the pandemic, with lockdowns and other practical restrictions on travel and conducting research in effect, won Rossano over. Perhaps they could do a community study, he thought, which would bypass the focus on individual animals that had plagued animal cognition work in the past.

Now, just a few years later, the Dog Communication Project is the largest citizen science study ever conducted on animal communication, with 10,000 dogs and 700 cats from 47 countries across every continent except Antarctica, Rossano says. It turns out dogs and dog people have a lot to talk about.

‘Mad.’ ‘Ouch.’ ‘Stranger.’ ‘Paw.’

So says Bunny, the now world-famous dog button user, in a widely shared conversation with her owner, Alexis Devine. In the video, Bunny presses the button for “mad,” and when her mom encourages her to elaborate, she presses those additional words on her soundboard. And sure enough, when Bunny finally walks up to her mom, there is a foxtail stuck in her paw, a very painful, and potentially serious, issue.

It might sound too good to be true. Who among pet owners has never wondered what’s going on in their animal’s mind when their behavior suddenly changes? And who has never felt frustrated that communication with their animals is doomed? What makes Bunny — with her 8.5 million followers on TikTok and 2 million on Instagram — so special?

The push and pull between believers and skeptics has been a boon to Rossano’s study, as the button-using community continues to grow and provide him with more data and test subjects. Early results suggest that at least some dogs do grasp the meaning behind the buttons they push. But to get results that might convince believers and skeptics both, Rossano had to get around a common hurdle in animal communication studies — the “Clever Hans Effect.”

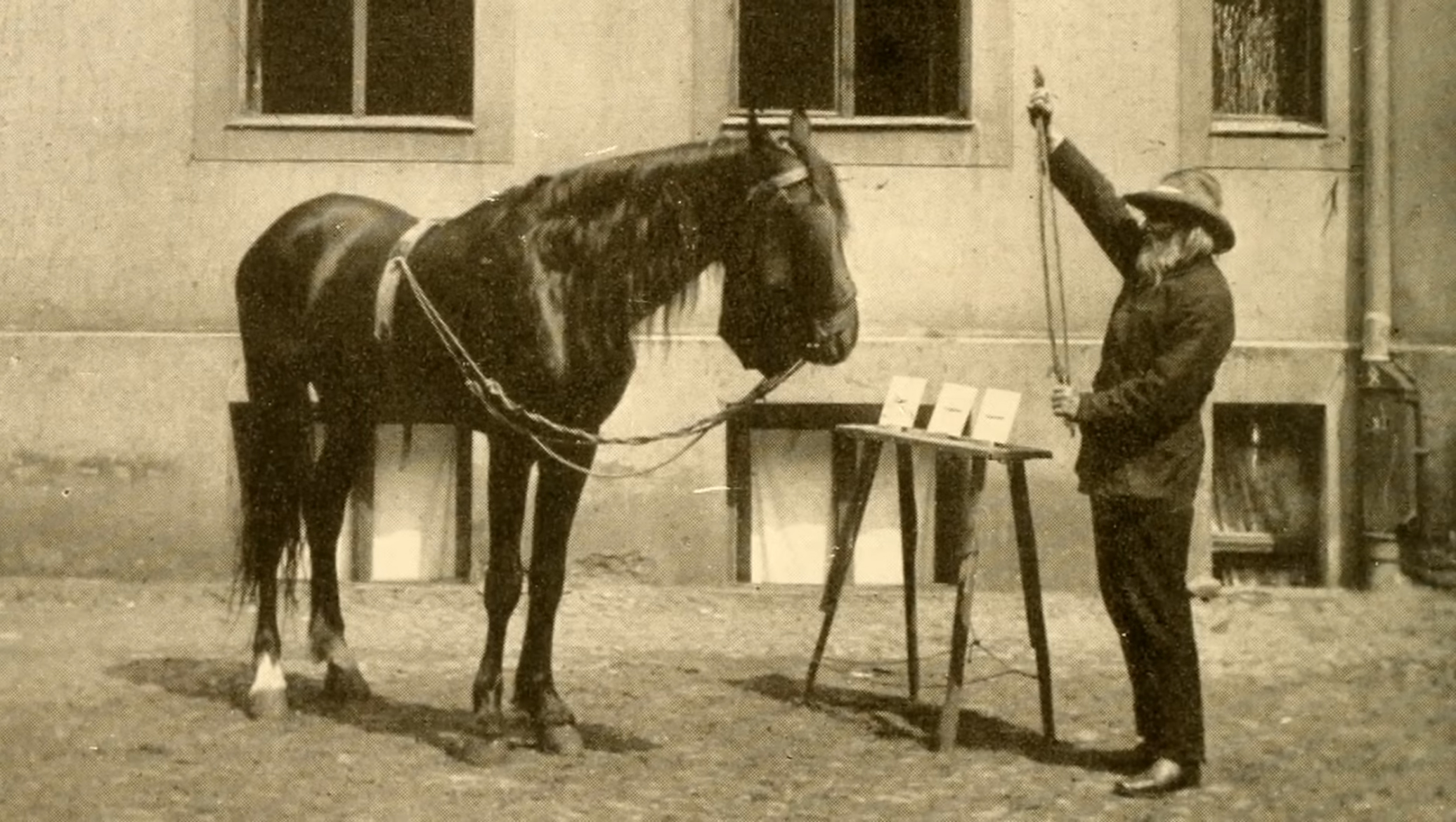

The horse that changed animal (and human) research

A century before Bunny and Stella, a horse named Clever Hans mesmerized the public, at least in Germany. Performing simple math and answering questions from his owner, teacher Wilhelm von Osten, Hans attracted so much interest at the time that the German Board of Education convened a committee to study him.

A laboratory assistant named Oskar Pfungst set about testing Hans’ intellectual capacity, inadvertently revolutionizing how psychological research is conducted. Pfungst’s process of isolating Hans from his handler showed just how important involuntary and unconscious cues can be. The horse was not in fact counting but was keenly observing his owner to produce the responses his owner wanted, Pfungst found. Hans was still remarkable — a Very Good Horse, if you will — but he was not engaging in the higher-level processing that signals language acquisition or mathematical ability. Pfungst’s insights into the importance of eliminating involuntary cues in research provided a model for future animal and human studies, including Rossano’s, though it did little to affect the popularity of Hans, who continued to draw crowds.

Several decades later, animal cognition research still struggled with the possibility of a Clever Hans effect, as well as the ethical quandaries that go along with separating a research subject from its natural environment. Most animal language scientists were still focusing on one particular animal per study; Koko the gorilla, for example, or Nim Chimpsky, a chimp whose moniker was a nod to linguist Noam Chomsky, a chief skeptic of animal language research who believes language acquisition is exclusive to humans. There were no control groups for these animals; each lived an unusual life, often isolated from members of their own species, and frequently exhibited unnatural and even unhealthy behaviors in response. Nim passed away at only 26, far shorter than his life expectancy in the wild.

Rossano’s study, on the other hand, allows its many subjects to be in their element — their owners’ homes. Using video cameras and recording devices to track thousands upon thousands of button presses from thousands of dogs, Rossano and his team have been able to collect quantifiable data while observing from afar. Even home visits to a select few dogs were designed so that the dogs could not pick up on cues. The goal was to isolate dogs’ interactions with buttons to better understand whether dogs could use their mastery of words exclusively to get what they want.

If pets could talk ...

What Rossano’s first published studies on the project have found is that indeed, some dogs seem to be able to grasp words as language in far more sophisticated ways than we previously thought. Notably, combinations like “outside” + “potty” or “food” + “water” were used in meaningful ways, occurring more frequently than expected by chance, with a much smaller subset of dogs, like Bunny, expressing more elaborate needs. Not all dogs catch onto or like the buttons, and most that do use only a few.

Take my dog, Donut, for instance — briefly featured in the Fig. 1 video, his role might have gone on a little longer if either of us had the motivation to attempt serious button learning. I taught him quite easily how to use a button with a word he already knows, “Treat!”

At the pinnacle of his button-using prowess, Donut would walk across a room to where the button was, pound it a few times, then coolly walk back to where I was to receive his bounty. He seemed to understand that the button was not a treat vending machine, but it was connected to my willingness to give him a treat. Not only was Donut not harmed in the making of the video — he might have been having one of the best days of his life. While Donut demonstrated that he was clever, his use of the button was simply a basic “if I do X, then Y” classical conditioning response. At that level, we both would have flunked button school, but many owners and animals work much harder.

Rossano cites at least 65 dogs in his study that use 100 or more buttons in a manner he would describe as regular communication. He cites a dog-owner exchange on video about using a swimming pool; the dog asks for “outside” and when the owner asks why, the dog presses “pool.” “Pool, later” the owner presses in response. “Now,” the dog responds. “Later,” the owner repeats. “Now,” the dog repeats again.

“It’s this back and forth we have published on,” Rossano says, describing how some dogs engage in negotiation in a way that provides evidence of communication.

“You don’t do that with a vending machine, right? If you hit ‘27’ and you don’t get Doritos, you don’t randomly hit other buttons expecting to receive Doritos. If you do this back and forth, like the dog did, you do this because you treat the other agent as somebody you can negotiate with, who could go your way if you can convince them. The dog is not treating you like a broken machine.”

The median number of buttons used by dogs in the study is 9; many of the dogs studied use only 3 or 4 buttons, and some just give up. But once dogs get past the mastery of familiar words such as “food,” “toy” and so on, their verbal world begins to resemble that of a toddler, who can produce two-word sentences after learning 50 words or so.

... they might talk about poop.

What dogs choose to communicate with their expanded vocabularies is both funny and intriguing. Dogs and human babies both seemingly go through a “poop” phase in which they love to initiate conversations about poop.

Like toddlers, dogs don’t simply use their words to mimic owners or make them happy: “Now” is a favorite dog word, in contrast to an owner’s generally preferred “later.” Dogs communicate “love” to their owners far less frequently than their owners do to them. Language strings are of particular interest: One dog in the study that had recently had a house visit from Rossano’s team asked its owner where the “treat stranger” was. Another famously pressed “squeaker” and “car” to seemingly signify an ambulance passing by. Still another had been pressing “water, bone” to request ice — up until the owner acquired an “ice” button and the dog abandoned its invented phrase.

More than 150 of the 10,000 dogs in Rossano’s published study have become capable of multi-button sequences; as of late 2024, that number has increased to 526, as described in this talk. Some of these presses are random; but the data strongly suggests many are not. Varied in size, shape and breed, these dogs, and cats, might allow us to learn more than we ever have before about what animals are capable of communicating, as a million button presses roll in every two months.

“This is why we are doing the study,” Rossano says. “To provide the public with an unbiased scientific assessment of what is going on with these dogs.”

“A dog is a dog, not a child. But that doesn’t mean that they might not have cognitive abilities resembling the cognitive abilities of a young child. And if that is the case, we should know because maybe that would lead us to conduct ourselves differently and care for their welfare differently.”

More resources

Learn more about Rossano’s research at his lab webpage. You and your pet can join Rossano’s study here.

UC San Diego: Dogs understand words from soundboard buttons, study reveals

UC San Diego: Dogs use two-word button combos to communicate, study shows

For a detailed lecture with Rossano about his study on cats and dogs, check out this video.