Keith Hamm, UC Santa Barbara

Thousands of songs representing some of the rarest and most uniquely American music borne from the Jazz Age and the Great Depression would have likely been lost to landfills and faded from memory. Fans and historians have long credited obsessive record collectors for preserving much of that music, and today they can thank a new partnership between UC Santa Barbara and the nonprofit Dust-to-Digital Foundation for making it available to the public for free.

UCSB Library’s Special Research Collections has been uploading music from the foundation’s trove of approximately 50,000 songs to the university’s Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR) database. So far, more than 5,000 songs from Dust-to-Digital have been added to DAHR, said David Seubert, curator of the library’s performing arts collection. “Thousands more are in the pipeline,” he noted.

“The Dust-to-Digital Foundation has digitized some of the most significant private collections in the country,” Seubert added. “We are pleased to partner with them to make this rare content accessible.”

Cofounded by Lance Ledbetter in 1999, Dust-to-Digital launched as a commercial label focused on preserving hard-to-find music and producing high-quality box sets, vinyl records, CDs, DVDs and books that share the detailed stories behind rare recordings. In 2010, Ledbetter and his wife, April, launched the label’s nonprofit foundation.

Over the years, the Ledbetters have worked closely with collectors to digitize and preserve record collections for educational purposes and public consumption. Earning trust and forging those relationships with often-reclusive collectors takes patience and an authentic appreciation of the music and its place in American history, April said. “We share their passion to keep our musical heritage from being forgotten.”

Once a relationship is established, Dust-to-Digital sets up special turntables and laptops in a collector’s home, with paid technicians painstakingly digitizing and labeling each record, one song at a time. Depending on the size of the collection, the process can take months, even years.

Along the way, the Ledbetter’s efforts have earned Grammys for Best Historical Album, in 2007, for “Art of Field Recording Volume 1: Fifty Years of Traditional American Music Documented by Art Rosenbaum” and, in 2019, Best Historical Album and Best Liner Notes for the box set, “Voices of Mississippi: Artists and Musicians Documented by William Ferris.”

“We’ve built our reputation through storytelling,” Lance Ledbetter said.

Seubert described the library’s partnership with Dust-to-Digital as a symbiotic coming together of an incredible music archive and the university’s established public-access platform.

Launched in 2008 and funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, DAHR (pronounced dar) has documented more than 440,000 master recordings made by record labels during the 78 rpm era, which spanned roughly 60 years starting in the late 1890s. The archive is known for its discographical details, artist bios, free streaming for noncommercial purposes and the high quality of its digitization in the Henri Temianka Audio Preservation Lab. Recordings in the public domain are also available for free download, in keeping with the UCSB Library’s mission for open access.

“The clarity and sound speaks for itself,” Ledbetter said.

Rare birds

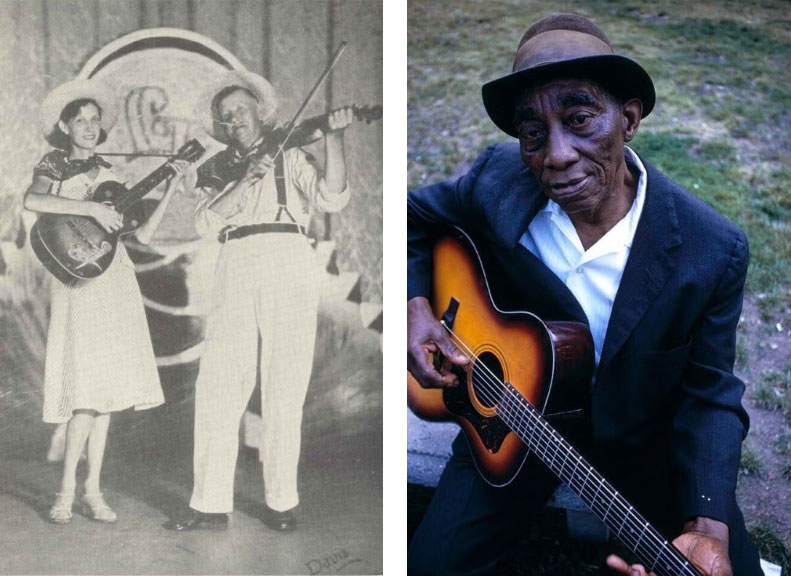

Included in the partnership’s release are two songs by Tennessee-born blues guitarist-singer Lane Hardin, who recorded “Hard Time Blues” and “California Desert Blues.” The songs, regarded as classics of the genre, appear on flip sides of a 78 rpm 10-inch released by Bluebird Records in 1936. Only a handful of copies are known to exist.

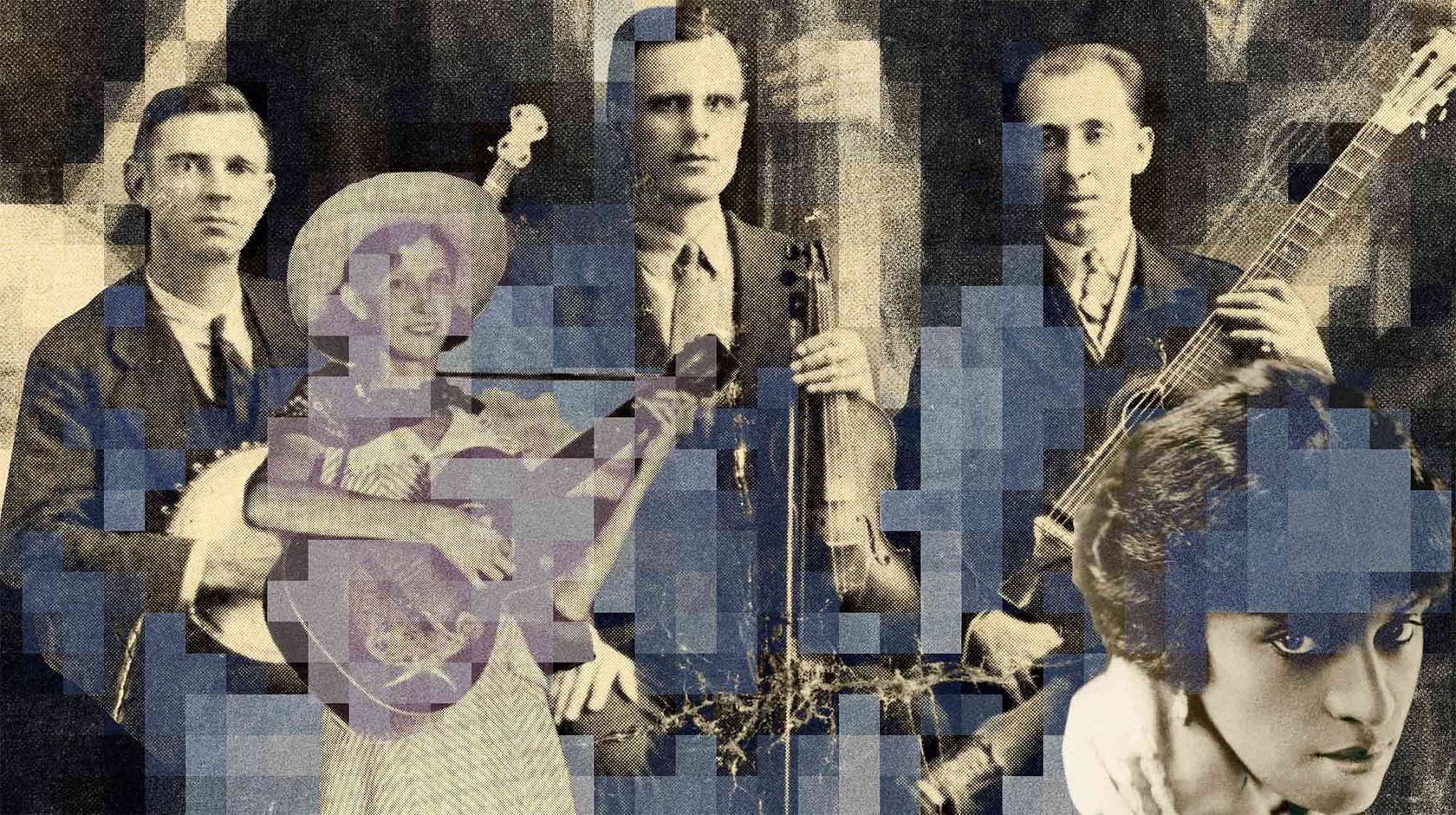

Also in the archive are recordings of guitarist-singer Memphis Minnie, singer and stage actress Eva Taylor, the Reverend J.M. Gates and country music pioneer Fiddlin' John Carson and his daughter, Rosa Lee Carson (popularly known as Moonshine Kate), who became an established solo artist and groundbreaking female performer in the genre.

“We felt it was important that this music come out in some fashion,” April Ledbetter said. “DAHR is a great home for music that doesn’t necessarily have a commercial market but is no less valuable to history.”

Slashdotted

As the Ledbetters remember it, they first crossed paths with Seubert decades ago at the annual conference of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections. In 2006, they heard about Seubert’s Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project getting “slashdotted,” a term that describes when a website crashes or receives a sudden and debilitating spike in traffic after being mentioned in an article on Slashdot, a popular news site at the time.

“We were aware of what David was doing with digitization,” Lance remembers. “He had been working for years to put wax cylinder recordings online through a public-facing institution — that was definitely on our radar.”

While the newly uploaded DAHR recordings come from multiple collectors — including Roger Misiewicz, Frank Mare and Kentucky-born folk artist Nathan Salsburg — the bulk belonged to Joe Bussard.

The Saint of 78s

Bussard grew up in Frederick, Maryland, dancing as a boy alongside the family Victrola and trading records with neighbors and friends. His early favorites were Gene Autry and Jimmie Rodgers, and his search for more of their music launched his 75-year obsession with record collecting.

Past the outskirts of Frederick and into the coal camps of Virginia and deeper south, Bussard scooped up 78s from rural general stores. Knocking door to door, he loaded his trunk with boxes and crates offloaded by families happy to part with dusty collections for some quick cash.

Increasingly, Bussard’s collection grew to include pioneering country string bands, jazz, bluegrass, cajun and gospel — many of the musical seeds from which sprung the popular songs of his beloved Jimmie Rodgers and the Singing Cowboy.

In “Joe Bussard: King of Record Collectors,” a 30-minute documentary produced by Dust-to-Digital in 2005, he’s portrayed as an archivist providing an invaluable culture service, his ever-growing collection preserving musical snapshots of traditional and often highly localized American music of the 1920s and 1930s. The era featured diverse musical dialects that existed only in small regions, sometimes even just a few adjoining rural counties. Musicians and historians note that if it wasn’t for the obsessive collecting of Bussard and others, much of this music would have vanished. When Bussard died in 2022, he left his family approximately 15,000 discs, the rarest among them could fetch several thousands of dollars from hardcore collectors.

“Joe had an exceptional collection that was built at a time when you could actually build something like that,” Seubert said. “You can't do that anymore. Even if you're fabulously wealthy, you could never end up with a collection that big and that good.”

Bussard wanted people to enjoy this music, Seubert added. “But you can't create a culture of enjoyment if they're all locked in archives, you know? There was a dichotomy between the collection being so good that it should be in a museum. But Joe didn’t want that. So Dust-to-Digital and UCSB have threaded that needle, making the music accessible to the public for free.”