2025 has been a tumultuous year for science. The federal government suspended, cancelled or delayed billions of dollars in funding to academic and government labs across the country. Courts have since paused or reversed many of these changes, but not before thousands of important research projects were affected.

The challenging environment hasn’t stopped University of California scientists from making their mark in 2025. Four UC faculty won the Nobel Prize, setting a new world record. And across all 10 UC campuses, researchers made progress against devastating diseases, invented new technologies, devised new ways to stay safe during disasters and shed light on the mysteries of the galaxy, our planet and our past.

Federal funding has made many of these and so many other UC breakthroughs possible by supporting research advances that improve lives, power America’s security and grow the country’s economic strength. That’s why UC leaders continue to speak up for science, urging Congress to invest in discovery and reject proposed cuts to federal science agencies in next year’s budget.

Read on to learn more about 10 amazing UC discoveries from the past year, brought to you by the incredible partnership between federal research funding and UC ingenuity.

Twin spacecraft depart for Mars

The first-ever UC Berkeley–led mission to Mars blasted off from Cape Canaveral in November. It’s now hurtling away on a three-year mission to map the magnetic fields of our nearest planetary neighbor and gauge how its atmosphere and ionosphere respond to space weather. NASA wants to know how these variables affect levels of DNA-damaging radiation on Mars’ surface — crucial information for any human who might someday set foot there.

Scientists at UC Berkeley's Space Sciences Laboratory and their partners in government and industry built and launched the mission’s twin spacecraft, appropriately named Blue and Gold, for about one-tenth the cost of NASA’s previous interplanetary missions. When they make it to Mars in 2027, Blue and Gold will spend a year in coordinated orbits, assembling a 3D view of how the planet’s atmosphere and ionosphere respond to changes in solar wind, the million-mile-per-hour stream of charged particles emanating from the sun. Alongside data that could affect human Mars explorers, the mission could also solve one of the biggest mysteries in space science: When and how did Mars lose the thick atmosphere that once blanketed the planet, holding in the abundant lakes and rivers that coursed its surface billions of years ago?

Made possible with funding from NASA

More from UC Berkeley: NASA’s ESCAPADE mission to Mars — twin UC Berkeley satellites dubbed Blue and Gold — launch in November

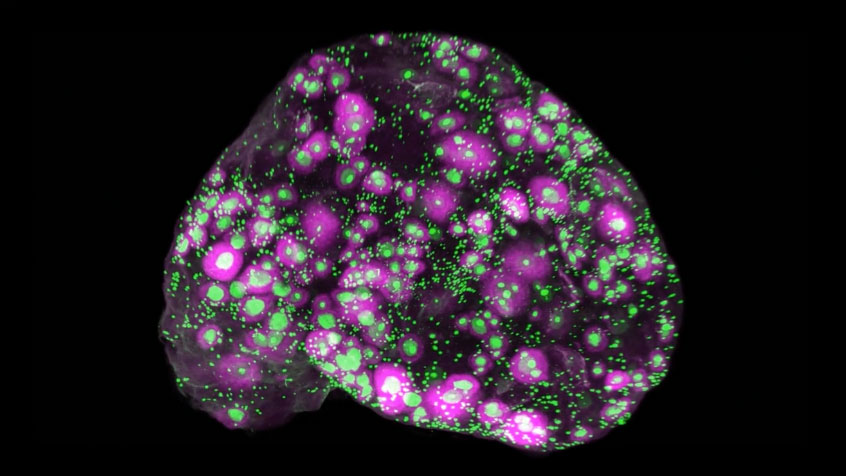

Gene editing enlists the brain’s immune cells to get medicines across the blood-brain barrier

A longstanding challenge in treating brain diseases, from Alzheimer’s to cancer to multiple sclerosis, is the blood-brain barrier. This natural defense system keeps harmful substances out, but also blocks most drugs from getting in. With funding from the National Institutes of Health, UC Irvine researchers found a workaround: They used CRISPR gene editing to turn microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, into programmable couriers. These engineered cells sense trouble, like the toxic protein plaques that define Alzheimer’s, and deliver therapeutic enzymes right at the source.

“This work opens the door to a completely new class of brain therapies,” says Robert Spitale, professor of pharmaceutical sciences at UC Irvine and co-corresponding author of a paper published in Cell Stem Cell in June. “Instead of using synthetic drugs or viral vectors, we’re enlisting the brain’s immune cells as precision delivery vehicles.”

Made possible with funding from the National Institutes of Health

More from UC Irvine: Scientists are using the brain’s immune cells to reimagine Alzheimer’s treatments

Deepfake video detection system could slow the spread of misinformation

A raft of new AI platforms has made it easier than ever for anyone with an internet connection to type in a few words and generate realistic videos depicting whatever scenario they can dream up. That makes for some interesting creative possibilities, but this brave new era also poses risks.

“It’s scary how accessible these tools have become,” says Rohit Kundu, a Ph.D. student at UC Riverside. “Anyone with moderate skills can bypass safety filters and generate realistic videos of public figures saying things they never said.”

Kundu and Amit Roy-Chowdhury, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, teamed up with Google to build one of the only fake-video detectors that’s keeping up with AI’s expanding capabilities. The Universal Network for Identifying Tampered and synthEtic videos (UNITE) examines not just faces but full video frames, including backgrounds and motion patterns. Kundu hopes to get the tool into the hands of social media companies, fact-checkers and newsrooms working to prevent fake videos from going viral.

More from UC Riverside: Scientists develop tool to detect fake videos

Guiding recovery from LA wildfires

No Angeleno who lived through it will ever forget the ordeal that began on Jan. 7, 2025, as flames fueled by hurricane-force winds tore through the communities of Altadena and the Pacific Palisades. As the fires raged, the UCLA community turned out en masse to serve meals, coordinate donations, and offer housing and support. In the months since, faculty and students in nearly every field have provided real-time information residents need to protect themselves from ongoing hazards, and to recover.

For instance, an early UCLA study found that climate change made LA’s landscape 25 percent drier on the eve of the fires, pinpointing climate as a key factor in the disaster’s severity. Nearly 20 faculty from UCLA, UC Davis and UC Irvine are part of the LA Fire Health Study, a long-term effort to track pollutants released by the fires over time and provide science-based guidance to residents about the health risks. And over 40 UCLA faculty joined an independent recovery commission that recommended dozens of specific critical policy actions to ensure an equitable and resilient recovery.

More from UCLA Magazine: Out of the ashes: How Bruin researchers are leading the way to mitigate future fire risk

A new medicine treats a deadly cancer in cats

Jak, a nine-year-old black cat, loved lounging under the Christmas tree, looking up at the lights. But Christmas was still months away when Jak’s family learned he had oral squamous cell carcinoma, one of the feline kind’s most aggressive and deadly diseases. The veterinarian said surgery, chemotherapy and radiation were no match for the condition, and gave Jak six weeks to live.

“It was just a gut punch,” said Tina Thomas, Jak’s mom. “We wanted more time with him.” So when she found out about a trial of a new drug for Jak’s disease at UC Davis, she enrolled him right away. The drug, developed at UC San Francisco, slowed disease progression in 35 percent of cats in the National Institutes of Health–funded trial, with few side effects. That’s great news for cats and the people who love them, and a good indication that the drug could also be safe and effective for humans with head and neck cancers.

Jak received weekly treatments for a month. His symptoms improved, and he went on to live comfortably for another eight months — long enough to spend another Christmas with his family.

Made possible with funding from the National Institutes of Health

More from UC Davis: New cancer drug could help cats and people

Jump-starting coral reef recovery

If Earth’s climate warms by two degrees Celsius in the coming decades — as it’s looking increasingly likely to do — the resulting changes in water temperature and chemistry could kill off 99 percent of the ocean’s coral reefs. With them would go habitat for a quarter of all marine species, fisheries that feed a billion people and natural barriers that protect 200 million people from the ocean’s wrath.

“I’m tired of hearing that corals are dying,” says UC San Diego marine biologist Daniel Wangpraseurt. “I’m more interested in what we can do about it.”

This year his lab solved one of reef restorations’ biggest hurdles: convincing skittish baby corals to settle on degraded reefs or human-built replacements. With funding from the U.S. Department of Defense, Wangpraseurt’s team formulated a UV-activated gel to coat underwater surfaces that releases coral-attracting chemicals. In lab experiments, the gel boosted coral colonies by a factor of 20 compared to untreated surfaces.

Made possible with funding from the U.S. Department of Defense

More from UC San Diego: New gel could boost coral reef restoration

What really causes women’s fertility to decline with age?

The average 25-year-old woman has about a 1 in 4 chance of getting pregnant in a given cycle. By the time she’s 40, those odds slide to less than 1 in 10. Scientists have mostly chalked this decline up to changes in just one type of cell: the egg. Women are born with all the eggs they’ll ever have, and these cells age and die on an inevitable trajectory from puberty to menopause. Or so the thinking goes.

Using new imaging and cell sorting techniques, UC San Francisco scientists found that declining fertility may be neither as simple nor as immutable as has long been believed. Among their surprise discoveries, published in the journal Science, was the presence in the ovaries of glia, a type of nerve support cell most studied in the brain. Other cells called fibroblasts triggered ovarian inflammation and scarring in women in their 50s — years earlier than such scarring appears in organs like the lungs or liver.

“This all points to a brand-new line of inquiry about how nerves, blood vessels, and other cell types communicate with eggs,” said UC San Francisco professor Diana Laird, who’s leading this National Institutes of Health-funded research. Her team is already studying whether drugs affect the timing or speed of these changes. That could lead to new treatments for infertility and other conditions, like cardiovascular disease, which are common in women after menopause.

Made possible with funding from the National Institutes of Health

More from UC San Francisco: Why does female fertility decline so fast? The key is the ovary

Reconstructing family histories for descendants of enslaved people

A lot of us have questions about our ancestors. For descendants of enslaved Africans, answers can be particularly hard to come by. Their families endured centuries of dislocation and separation under a legal system that recorded scant details about their lives. So the historical record is sparse, and consumer genetic testing databases often lack sufficient samples from people living in Africa today to give users reliable information about their heritage on the continent.

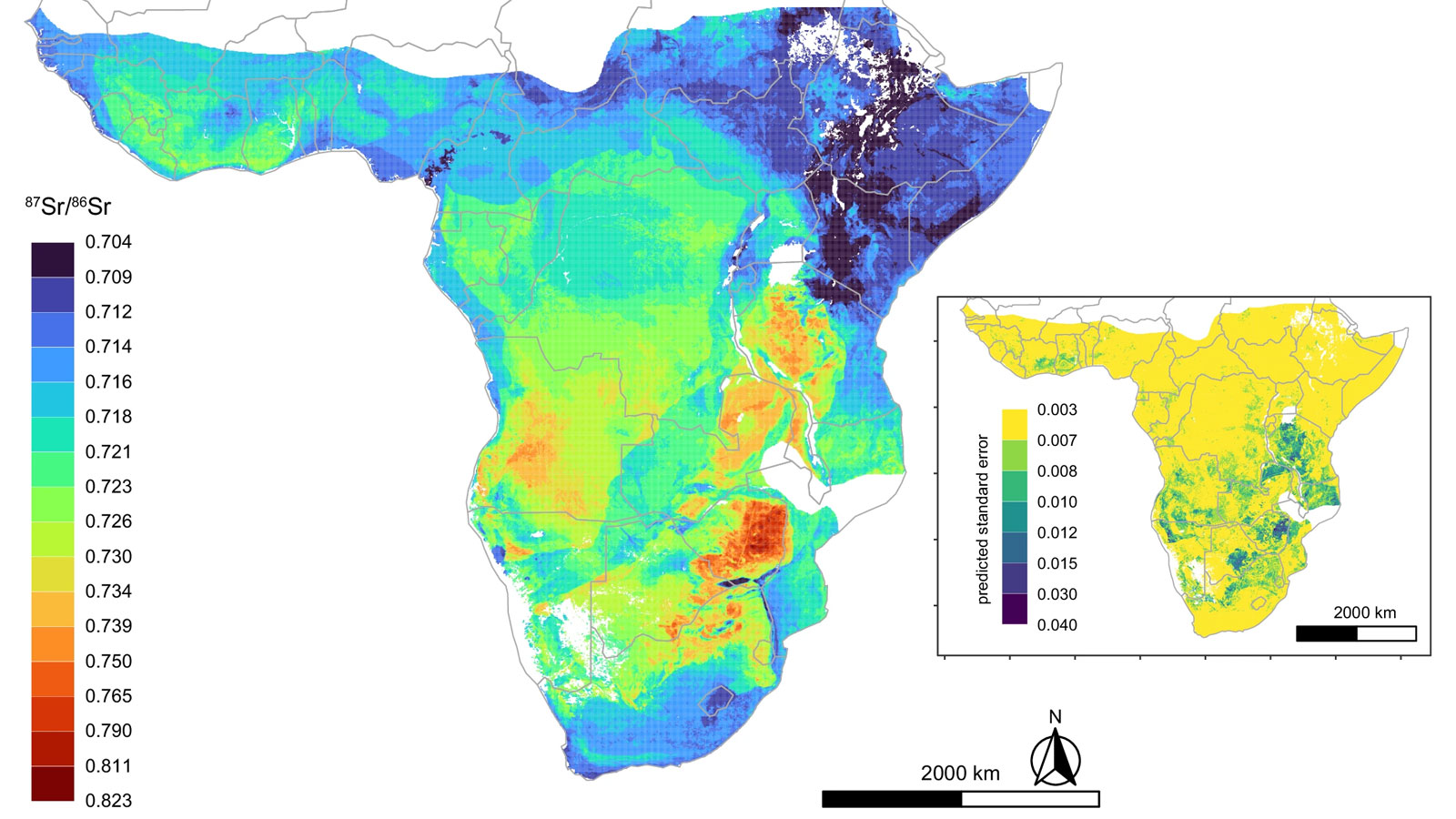

A new map created by UC Santa Cruz archaeologists is helping pinpoint where in Africa people lived before enslavers captured them and brought them to the Americas. The map charts variations, or isotopes, of an element called strontium. The rocks and soil of any given spot on Earth contain a distinctive mix of strontium isotopes, and this strontium signature carries into local drinking water and food, and then into the bodies of people and animals who grow up there. After a person dies, their homeland’s strontium signature can linger in their bones and teeth for hundreds of years.

Archaeologists working with descendant communities in the U.S. can determine the mix of strontium isotopes in remains from known burial grounds to identify first-generation enslaved people. That information can now be cross-referenced with the new map of strontium signatures compiled from more than 2,000 biological and soil samples collected across Africa, to zero in on where on the continent enslaved people lived before arriving in the Americas.

“That tells us something about a person’s life history to help us better understand these ancestors and how their legacies contribute to living populations today,” says UC Santa Cruz anthropologist Vicky Oelze, who led an international team of over 100 scientists to create the map.

More from UC Santa Cruz: New strontium isotope map of Sub-Saharan Africa is a powerful tool for archaeology, forensics, and wildlife conservation

A cause of — and a solution to — dangerous dust storms

California’s 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act regulates how much water utilities and farmers can pump from underground aquifers. The law has succeeded in protecting an important natural resource that meets about half the state’s needs for drinking and irrigation, “which is important for California’s future,” said UC Merced professor Adeyemi Adebiyi. “However, there are unintended consequences to nearby communities.”

For one thing, it has caused some farmers to leave more land unplanted. Without crops to hold the topsoil in place, it’s likelier to blow away on windy days, contributing to worsening dust storms. These storms can roar up without warning, catching drivers off-guard and causing traffic accidents. Breathing dusty air is hard on people with asthma and can expose communities to communicable diseases such as Valley fever.

In a 2025 study supported by the State of California and the U.S. Department of Energy, Adebiyi’s team at UC Merced found that the Central Valley now accounts for about 77% of fallowed land in California and is associated with about 88% of serious dust storms. It’s possible to reduce risk without rolling back groundwater regulations: for instance, Adebiyi suggests farmers plant cover crops on fallowed land instead of leaving it bare.

Made possible by the U.S. Department of Energy and the State of California

More from UC Merced: Study indicates human-caused dust events are linked to fallow farmland

Faster, safer emergency intubation

Intubation — the high-stakes process of threading a breathing tube down a patient’s throat to maintain an open airway — is a tricky procedure. The provider has to move aside the flap of tissue at the back of the patient’s mouth that separates the esophagus from the trachea, then route a stiff tube on an invisible path through delicate tissue toward the lungs. It’s one thing for an experienced doctor to pull off this maneuver in a hospital, and quite another for a first responder at the chaotic scene of an emergency, when seconds count.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, UC Santa Barbara mechanical engineers invented a device that solves some of these challenges. It starts with a curved “introducer” that slides into place at the back of the throat, carrying a soft, inflatable tube that gently extends down into the trachea. Once the tube is fully in place, an inflatable cuff seals off the opening, the introducer can be removed, and ventilation can begin.

In initial tests, 100 percent of experienced providers got the device working within seconds. EMTs and paramedics got it on the first try 87 percent of the time and eventually succeeded in 96 percent of tries. And it took these first responders just 21 seconds to place the soft tube, less than half the average time it took them to intubate using current state-of-the-art methods.

Made possible with funding from the National Science Foundation

More from UC Santa Barbara: Soft robot intubation device could save lives