Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

You might have heard us talking about it lately, but in case you missed the big news, the University of California set a new world record for Nobel Prizes this year.

In October the Nobel Committee recognized three UC physicists for their decades of progress in quantum computing and a UC chemist whose new molecular architecture can wring water out of thin air. The committee also recognized an alum of both UC San Diego and UCLA whose work is helping prevent the immune system from attacking the body’s own tissues.

The laureates are in Stockholm this week to collect their medals, and it’ll be the first time that four faculty from a single institution have ever been recognized in a single year. These wins bring the number of Nobels awarded to UC faculty to 75, a number that few other universities on Earth can match.

What makes the University of California such a powerhouse for history-making discoveries? We’re big, for one thing: with ten campuses, three national labs, six academic health centers and programs in every county in California, we’re proud to serve and represent America’s most populous state.

But these numbers aren’t the whole story. They don’t explain why UC consistently tops independent national and global rankings of entrepreneurialism, innovation, influential scholarship, research opportunity and research impact. All this excellence reflects the spirit and ambition of the Golden State, a place where people from all over the world come to bring their best ideas to life. It’s also a place where our homegrown talent can learn and grow at the nation’s best public university, which also offers America’s best value in higher education.

A few weeks ago, four of UC’s Nobel laureates spoke to the UC Board of Regents about what they discovered here, why it matters, and why their world-changing work could only have happened at the University of California.

UCLA astronomer and Nobel laureate Andrea Ghez

“At the University of California, we have the tools to look deep into the universe, and we've been able to bring something incredible into focus. We showed the world something that’s impossible to see directly and discovered more questions than answers.”

Andrea M. Ghez, 2020 Nobel laureate in physics, professor of physics and astronomy at UCLA

Physicists and astronomers had long theorized the existence of a black hole at the center of the Milky Way, but nobody knew how to prove it — until UCLA’s Andrea Ghez got behind the wheel of the Keck Observatory.

Co-owned by UC and CalTech, these twin telescopes are the biggest and most powerful astronomical instruments on Earth. “They’re like modern-day pyramids,” Ghez said, and they’re a big part of why UC employs one in five researchers working in astronomy and astrophysics today.

Thirty years ago, Ghez came to UCLA to figure out how to use the Keck telescopes to measure the orbital speed and size of stars swirling around the heart of our galaxy. Those observations eventually gave her team enough information to calculate the mass and volume of the object the stars were orbiting around, findings that “have moved the notion of a supermassive black hole from a possibility to a certainty,” Ghez said. This achievement earned her the Nobel prize in physics in 2020.

The discovery answered one of astronomy’s biggest questions — and forced scientists to start asking a whole lot more, since the existence of black holes defies the laws of fundamental physics. “That’s what we do at the University of California every day,” Ghez said. “We ask questions, we explore things that are still shrouded in darkness, and we bring new knowledge and understanding into focus.”

UC San Francisco professor of physiology David Julius

“UC is a special place where people interact freely. There are other places I could have gone that could have given me more resources. What they couldn't give me was the intellectual and collegial atmosphere, working with scientists who mentored me to be curious and active in the scientific community and to give back.”

David Julius, 2021 Nobel laureate for physiology or medicine, UC Berkeley Ph.D. and professor of physiology and molecular biology at UC San Franscisco

David Julius had what sounds, at first pass, like a simple question: How do we feel sensations like heat, cold, and pain? “As scientists, we’re curious,” Julius said. “We want to understand how our sensory system works, because it's how we experience the world.”

With support from the National Institutes of Health, Julius and his UC San Francisco lab used capsaicin, the compound that makes chili peppers spicy, to pinpoint the protein on the surface of our nerve endings responsible for sensing both heat and spice. Julius’s work also revealed similar proteins responsible for sensing cold using mint, and for inflammation-based pain using wasabi.

“One thing that illustrates the power of a place like UC is that my colleagues at UCSF are pioneers in methods looking at molecules at their atomic level,” Julius said, information that can speed up the search for new classes of pain medicines that act on the proteins his team has discovered.

“We hope that the molecules that we and other people have identified can be targets for new types of therapeutic, nonaddictive, nontoxic drugs,” Julius said.

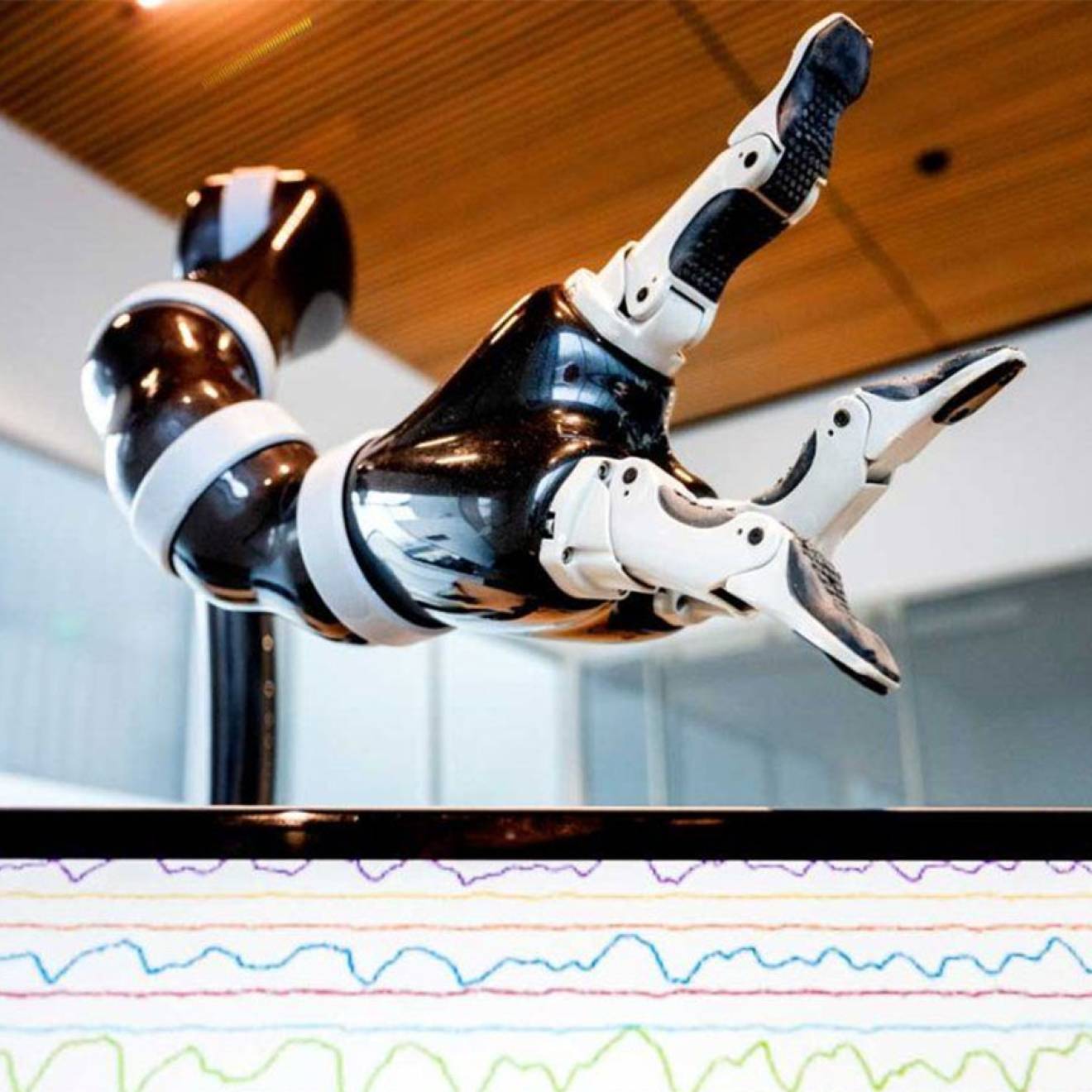

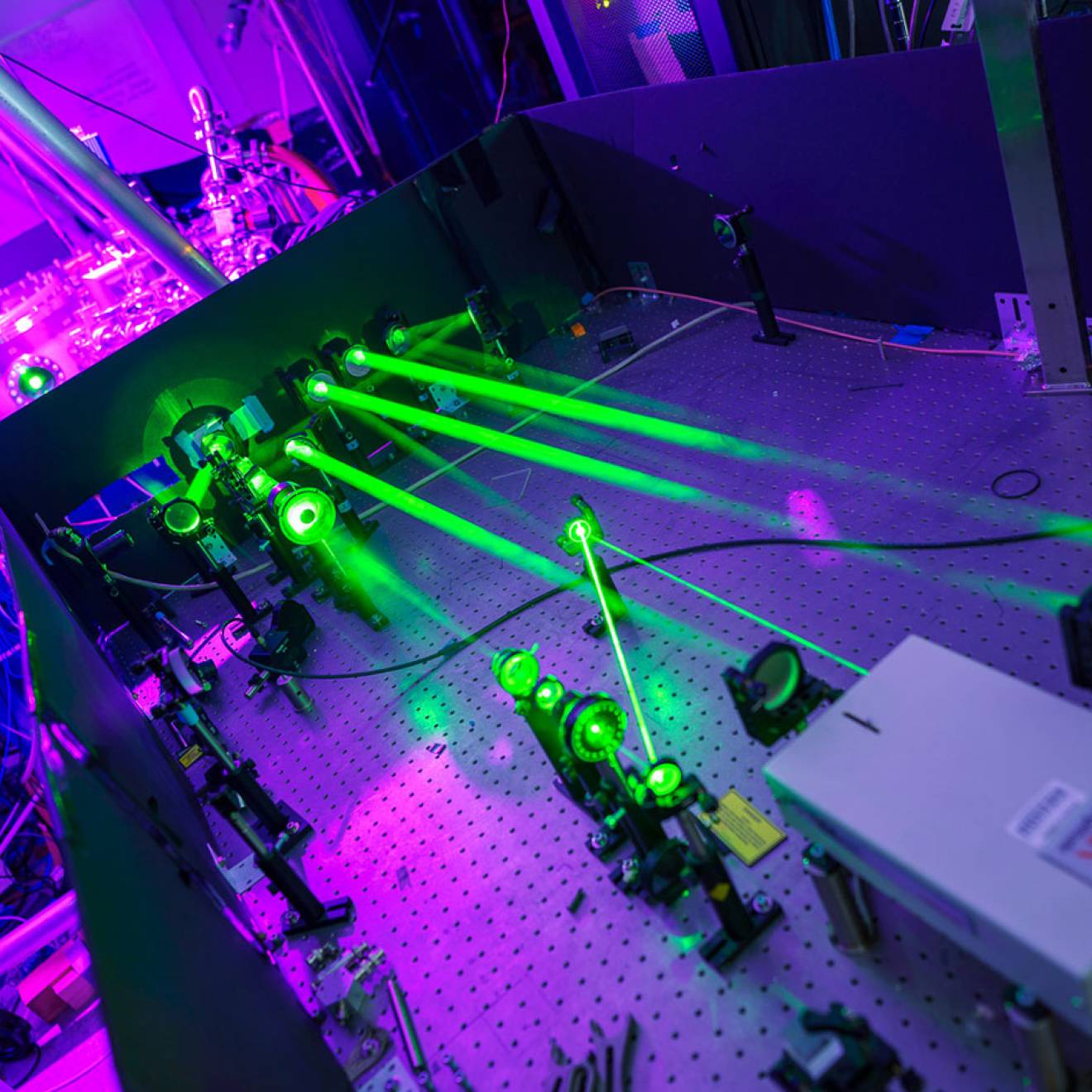

John Martinis, professor emeritus of physics at UC Santa Barbara

“When I went to UC Berkeley, it was amazing to be taught by the top physicists in the world. And they were all experts in building the instruments that lead to scientific discovery.”

John Martinis, 2025 Nobel laureate for physics, UC Berkeley B.S. and Ph.D., professor emeritus of physics at UC Santa Barbara

Martinis is part of UC’s record-setting 2025 class of Nobel laureates, alongside UC Santa Barbara professor Michel Devoret and UC Berkeley's John Clarke and Omar Yaghi. In the 1980s, Martinis was a grad student and Devoret was doing his post-doc in Clarke’s lab at Berkeley, batting around a question posed by renowned physicist (and eventual Nobel laureate) Anthony Leggett. Leggett had already done a lot to advance the theory of quantum physics, the discipline that describes the bizarre properties of sub-atomic particles. But the field was struggling to reconcile Leggett’s theories with the observable behavior of everyday objects and systems.

“Maybe the resolution to this is that macroscopic systems can’t obey quantum mechanics for some reason. Leggett said that would be a good experiment,” Martinis said. To actually run it, someone would have to try to build a macroscopic system that obeyed quantum theory. That’s what Martinis, Clarke and Devoret eventually did, demonstrating both quantum tunneling and quantized energy levels in a circuit large enough to be held in the hand.

“To get the experiment to work we had to think about microwave electronics, which we had access to thanks to the astronomy department at UC Berkeley, and we had to define things right and do it carefully and operate at this at very low temperatures in what is called a dilution refrigerator,” Martinis said. “I won’t go too into the details of that.” The point is, Martinis’s team was part of an institution where people don’t just ask thorny, theoretical questions. They also roll up their sleeves and build the complex, finicky, never-before-imagined thing that can get answers.

Martinis’s experiment gave scientists the ability to generate, probe and exploit macroscopic quantum behaviors. That has opened the door to advanced technologies, from quantum information processors to quantum sensors that enable highly precise measurement, to quantum computers that will soon be able to solve complex practical problems.

Randy Schekman, professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley

“California’s master plan for higher education included the construction of new campuses large enough for the children of all the families of our state to enjoy the nation’s finest educational opportunities. I was a direct beneficiary of that investment.”

Randy Schekman, 2013 Nobel laureate for physiology or medicine, professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley

Randy Schekman’s lifelong fascination with biology began the minute he squinted into a toy microscope at his family’s kitchen table in Southern California and saw “the amazing microbial world of single cell organisms crawling and swimming around my vision,” he said. He wanted to zoom in further, but his parents didn’t have enough money to buy him a better microscope. So he saved up money from mowing his neighbor’s lawn to buy his own from a local pawn shop.

That fascination carried him off to college at UCLA in the 1960s, a time when California was massively expanding its public higher education system. “I was from a middle-class family where college was an expectation, but money was a concern,” Schekman said. “No private school for me, but UCLA was great.” As a first year, he did research in the lab of Willard Libby, the 1960 Nobel laureate in chemistry. And for $6.25, he bought season tickets to watch Kareem Abdul-Jabbar carry the Bruins to three straight NCAA titles.

As a young professor at UC Berkeley, Schekman set out to study how proteins get from the cells where they're made to the places they’re needed in our bodies. Studying a single-cell organism, baker’s yeast, he discovered the genes and molecules that control how cells package and transport proteins through the cell wall. The same genes and proteins his lab discovered in yeast have been found to operate throughout our body to organize the secretion of hormones, antibodies, neurotransmitters, and all the things the human body uses for normal physiology.

After his initial discovery, Schekman helped a biotechnology company engineer yeast to manufacture and secrete large quantities of useful proteins, such as human insulin to manage diabetes and the hepatitis B vaccine. Today a third of the world’s supply of recombinant insulin comes from yeast.

UC's Nobel legacy

The University of California has been winning Nobel Prizes since 1939, when Ernest O. Lawrence was awarded the prize in physics for his invention of the cyclotron. Meet UC’s 74 Nobelists.

The 2025 Nobel laureates are giving talks about their work as part of this week's awards celebrations in Stockholm. Watch UC faculty and alumni describe their discoveries in physiology or medicine, physics and chemistry.